Railroad Part 3

The Los Angeles Terminal Railway was not organized just for the convenience of local businesses, commuters and tourists. Thomas E. Gibbon actively pursued possible financial backers to fund the construction of a railroad line from the Terminal properties to Salt Lake City. It was an ambitious attempt to bring a new transcontinental line into Southern California but the Terminal lacked the capital to build the line. He met with E. H. Harriman of the UP in Seattle for backing but was unsuccessful. Eastern capitalists were approached but wanted no competition with the Southern Pacific and Santa Fe. Gibbon finally found success with J. Ross Clark, a Los Angeles banker who had an office next door to his. It was widely known that Clark and his brother, William A. Clark of Montana, were investing heavily in Southern California development.

J. Ross Clark was interested enough to submit the Terminal road’s plans to his brother for approval. You could say that this meeting was the turning point in the history of the Salt Lake Route. The gears meshed and the project started moving forward.

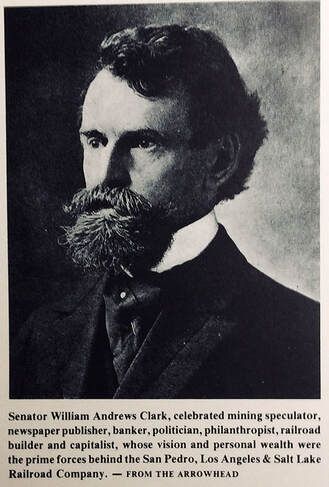

A short history on William A. Clark: He was known as the “Copper King”. He was born in Pennsylvania and his energy and ambition were legendary. He studied law at Iowa Wesleyan College and ended up teaching school in Missouri. With a small savings he left Missouri for Central City, Colorado, where he worked as a mucker in the mines for $2.50 per day.

As the Civil War commenced, he used his wits and ingenuity to build a fortune for himself. When gold was discovered in Bannack, Montana, he used oxen instead of horses to get there knowing he could sell the oxen for meat. Flour and tobacco were in short supply in the camps so he saw an opportunity to prosper from the situation. In the process he acquired the name of Baking Powder Billy. He established a star route mail line from Missoula to Walla Walla, Washington and achieved prominence. Clark’s honesty and financial genius helped him establish a merchandising business and bank at Deer Lodge, Montana in 1869.

He became interested in the underdeveloped mines in Butte and gained control over the rich mineral deposits located there. About the same time, he acquired sole ownership of the United Verde mines at Jerome, Arizona. It seemed he had the “Midas Touch” as everything he invested in turned to gold. His interests included the Butte Electric Railway, Los Alamitos Sugar, Western Montana Flouring, a number of newspapers in Montana and Utah, a wire works at Elizabeth, New Jersey, the United Verde & Pacific Railway and many more. He became one of the wealthiest men in America.

A short history on William A. Clark: He was known as the “Copper King”. He was born in Pennsylvania and his energy and ambition were legendary. He studied law at Iowa Wesleyan College and ended up teaching school in Missouri. With a small savings he left Missouri for Central City, Colorado, where he worked as a mucker in the mines for $2.50 per day.

As the Civil War commenced, he used his wits and ingenuity to build a fortune for himself. When gold was discovered in Bannack, Montana, he used oxen instead of horses to get there knowing he could sell the oxen for meat. Flour and tobacco were in short supply in the camps so he saw an opportunity to prosper from the situation. In the process he acquired the name of Baking Powder Billy. He established a star route mail line from Missoula to Walla Walla, Washington and achieved prominence. Clark’s honesty and financial genius helped him establish a merchandising business and bank at Deer Lodge, Montana in 1869.

He became interested in the underdeveloped mines in Butte and gained control over the rich mineral deposits located there. About the same time, he acquired sole ownership of the United Verde mines at Jerome, Arizona. It seemed he had the “Midas Touch” as everything he invested in turned to gold. His interests included the Butte Electric Railway, Los Alamitos Sugar, Western Montana Flouring, a number of newspapers in Montana and Utah, a wire works at Elizabeth, New Jersey, the United Verde & Pacific Railway and many more. He became one of the wealthiest men in America.

As a result of several meetings with Clark, T. E. Gibbon was able to persuade him to invest in a railroad line from Los Angeles to Salt Lake.

After much discussion and careful planning, San Pedro harbor was selected as a more advantageous port for trade and shipping. It was even assumed that it would surpass San Francisco in importance. Also, by building the line to Salt Lake along the proposed route they would have lighter grades, wider curvatures, a minimum of bridges and trestles and the absence of heavy snows along most of the road and thus be cheaper to operate. Safety and comfort were also major factors.

Clark was also aware of the iron ore, gold, silver, lead and coal deposits in Utah and realized the strategic importance of a railroad to service these areas. He was convinced that considerable profits could be made by investing in this venture, so on August 21, 1900, officials of the Los Angeles Terminal Railway formally announced William A. Clark of Montana had acquired a sizable interest in their company with the intention of building a railroad to Salt Lake City. When the news of this proposed project was made public, the Union Pacific and Southern Pacific Were not happy. The Oregon Short Line had long considered this route as its own domain. In fact, the Union Pacific and Oregon Short Line had made early surveys of the line in 1881 and 1889.

After much discussion and careful planning, San Pedro harbor was selected as a more advantageous port for trade and shipping. It was even assumed that it would surpass San Francisco in importance. Also, by building the line to Salt Lake along the proposed route they would have lighter grades, wider curvatures, a minimum of bridges and trestles and the absence of heavy snows along most of the road and thus be cheaper to operate. Safety and comfort were also major factors.

Clark was also aware of the iron ore, gold, silver, lead and coal deposits in Utah and realized the strategic importance of a railroad to service these areas. He was convinced that considerable profits could be made by investing in this venture, so on August 21, 1900, officials of the Los Angeles Terminal Railway formally announced William A. Clark of Montana had acquired a sizable interest in their company with the intention of building a railroad to Salt Lake City. When the news of this proposed project was made public, the Union Pacific and Southern Pacific Were not happy. The Oregon Short Line had long considered this route as its own domain. In fact, the Union Pacific and Oregon Short Line had made early surveys of the line in 1881 and 1889.

The UP’s plans were thwarted by Collis P. Huntington, who made it known that if the Union Pacific attempted to build its line south of Uvada, the Southern Pacific would counter by building their own line to Salt Lake. When Harriman gained control of the Union Pacific in 1899, the plans to extend the Oregon Short Line into Southern California were revived. Construction was imminent so the OSL took control of the old Nevada Pacific grade again and incorporated the Utah, Nevada & California to build the line from Milford to the Nevada/California state line.

Clark forged ahead with his plans to build his road and organized the Empire Construction Company which would build the line, and the Utah & California Development Company which would be responsible for land sales and industrial development along the proposed route. Not to be left out of the fray, on December 12, 1900, Huntington and the Southern Pacific warned that the SP and Santa Fe would each have a Line from Los Angeles to Salt Lake before Clark even started construction. Clark ignored their threats and on January 14, 1901, the stockholders of the California Improvement Company met in St. Louis, and transferred most of the control of the Los Angeles Terminal RY to form a new organization to be known as the San Pedro, Los Angeles & Salt Lake Railroad. It was also at this same time that Clark was elected to the US senate from Montana.

The San Pedro, Los Angeles & Salt Lake RR was incorporated under the laws of Utah on March 20, 1901. This date marked the official beginning of the SPLA&SLRR. Additional filings in Nevada and California took place on April 8, 1901. Clark was aware of the hostile environment he was entering as E. H. Harriman of the Union Pacific warned him that he would have a fight on his hands if he attempted to build his line.

Clark forged ahead with his plans to build his road and organized the Empire Construction Company which would build the line, and the Utah & California Development Company which would be responsible for land sales and industrial development along the proposed route. Not to be left out of the fray, on December 12, 1900, Huntington and the Southern Pacific warned that the SP and Santa Fe would each have a Line from Los Angeles to Salt Lake before Clark even started construction. Clark ignored their threats and on January 14, 1901, the stockholders of the California Improvement Company met in St. Louis, and transferred most of the control of the Los Angeles Terminal RY to form a new organization to be known as the San Pedro, Los Angeles & Salt Lake Railroad. It was also at this same time that Clark was elected to the US senate from Montana.

The San Pedro, Los Angeles & Salt Lake RR was incorporated under the laws of Utah on March 20, 1901. This date marked the official beginning of the SPLA&SLRR. Additional filings in Nevada and California took place on April 8, 1901. Clark was aware of the hostile environment he was entering as E. H. Harriman of the Union Pacific warned him that he would have a fight on his hands if he attempted to build his line.

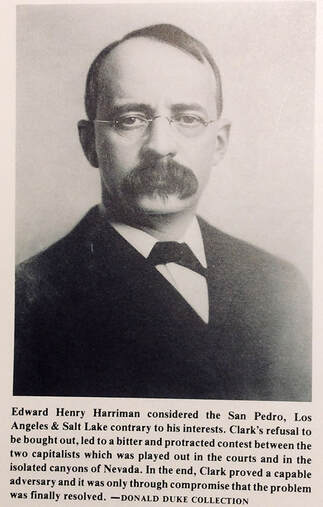

Now for a short history of E. H. Harriman: Edward Henry Harriman was born in upstate New York in 1848. He started a career on Wall Street at the age of 14, and by 1870 he owned his own brokerage firm. By 1880 he had ventured into railroad securities. Because of his financial genius, by 1900 the name of Harriman was one of the most feared and formidable in the railroad industry in the United States. He either controlled or sat on the board of directors of the Illinois Central, Erie, Union Pacific, Chicago & Alton, Kansas & Southern and the B&O.

After taking control of the UP, it grew into one of the strongest and most successful railroads in the country and still is to this day. He reorganized the bankrupt railroad and reunited all the lines of the former system, including the Oregon Short Line. Ignoring Clark and his intended railroad at this time, he was less interested in building the line from LA to SLC than he was with his current goal of gaining control of the Southern Pacific. But after the SPLA&SL was incorporated he offered to buy out Clark and all his interests for a cost of 5 million dollars with an additional $250,000 to cover the costs of organizing the Empire Construction Co., Utah & California Development Co. and the corporation that would own and operate the railroad. Clark refused and prepared for a fight.

A month before the incorporation of the SPLA (which is what I will call it from now on), Harriman and the UP acquired a large block of Southern Pacific stock and by the end of 1901 the UP owned 45.5% of the SP. This merger caught Clark by surprise, but showing no fear or concern, he announced his intentions to proceed with his plans to build his railroad.

After all the surveys, Clark chose the route through Meadow Valley wash rather than the safer route through Panaca, Pioche and Bristol Pass, a decision that would cost the railroad dearly in the coming years. He wasted no time on taking advantage of resources that were available. The OSL had taken over the old Nevada Pacific grade but defaulted on the taxes. Clark and his associates acquired the Utah & California, an inactive corporation chartered in Utah in 1896, and through this company he bought the tax title. He now had possession of the Nevada Pacific including 6 completed tunnels and on April 19, 1901, full control of the road passed to the Salt Lake Route.

Harriman retaliated quickly. W. H. Bancroft, general manager of the OSL, announced that the line from Salt Lake to Uvada would be extended to Los Angeles. Soon after, J. Q. Barlow of the OSL, along with surveyors and contractors, were traveling south from Uvada to plan a 400 mile route to connect with the Southern Pacific in California.

After taking control of the UP, it grew into one of the strongest and most successful railroads in the country and still is to this day. He reorganized the bankrupt railroad and reunited all the lines of the former system, including the Oregon Short Line. Ignoring Clark and his intended railroad at this time, he was less interested in building the line from LA to SLC than he was with his current goal of gaining control of the Southern Pacific. But after the SPLA&SL was incorporated he offered to buy out Clark and all his interests for a cost of 5 million dollars with an additional $250,000 to cover the costs of organizing the Empire Construction Co., Utah & California Development Co. and the corporation that would own and operate the railroad. Clark refused and prepared for a fight.

A month before the incorporation of the SPLA (which is what I will call it from now on), Harriman and the UP acquired a large block of Southern Pacific stock and by the end of 1901 the UP owned 45.5% of the SP. This merger caught Clark by surprise, but showing no fear or concern, he announced his intentions to proceed with his plans to build his railroad.

After all the surveys, Clark chose the route through Meadow Valley wash rather than the safer route through Panaca, Pioche and Bristol Pass, a decision that would cost the railroad dearly in the coming years. He wasted no time on taking advantage of resources that were available. The OSL had taken over the old Nevada Pacific grade but defaulted on the taxes. Clark and his associates acquired the Utah & California, an inactive corporation chartered in Utah in 1896, and through this company he bought the tax title. He now had possession of the Nevada Pacific including 6 completed tunnels and on April 19, 1901, full control of the road passed to the Salt Lake Route.

Harriman retaliated quickly. W. H. Bancroft, general manager of the OSL, announced that the line from Salt Lake to Uvada would be extended to Los Angeles. Soon after, J. Q. Barlow of the OSL, along with surveyors and contractors, were traveling south from Uvada to plan a 400 mile route to connect with the Southern Pacific in California.

In April 1902, Clark dispatched a train of laborers to Uvada to begin construction on what he thought was his grade. Unbeknownst to Clark, E. E. Calvin of the OSL sent his own crew to the same location with the same intentions. They left in a special train and overtook Clark’s train at Milford. When Clark’s forces arrived on April 7, Calvin’s crews were already working to restore the grade. The race was on and having lost the advantage, Clark’s workers moved 2 miles south of Uvada to hold the SPLA claim on the Nevada side. Joseph Young, superintendent under E. E. Calvin, promised Clark’s crews higher wages so some of his laborers defected over to the OSL. Clark’s forces attempted to hold the line against the OSL camp, but a fight ensued and Clark’s workers were overwhelmed and they moved farther down the grade to resume work. The battle of Clover Creek canyon, as it came to be known, resulted in nothing but bloody noses and harassment from both sides. Work continued unabated.

The old NP grade was still intact but in need of repair. Ties and rails were distributed along the tracks at every siding from Juab south, enough to build 100 miles of railroad grades. The Short Line held the advantage in Clover Creek canyon but were treading on thin ice legally. Meanwhile, Harriman was behind the scenes challenging the validity of the SPLA tax title. He met with Judge T. P. Hawley and persuaded him to declare Clark’s tax title as invalid, citing an obscure law that dealt with construction in Nevada by out-of-state companies. He contended that the Utah & California Company had committed fraud and convinced the judge to rule in his favor. He prevailed and on April 24, 1901, General Land Office officials in Washington reversed the decision of Nevada officials in Carson City which issued Clark’s permits. The Utah & California was blocked and the Short Line, who held prior rights, took control of the NP and the Utah & Pacific grades. On April 27, Harriman obtained an injunction which blocked Clark from interfering with the OSL construction in Clover Creek canyon. There was a little known law which prevented a railroad from monopolizing mountain passes and canyons, so Harriman could now build a line parallel to Clark’s in the canyon. Position was critical and they were both concerned over who would get the best grades in the narrow canyon. Clark didn’t rest and moved in a different direction, buying the tax title to the grade from Pioche to Clover Valley junction, and from there to Uvada. Because Clark couldn’t build in Clover Creek canyon he moved his camp to Meadow Valley wash.

The old NP grade was still intact but in need of repair. Ties and rails were distributed along the tracks at every siding from Juab south, enough to build 100 miles of railroad grades. The Short Line held the advantage in Clover Creek canyon but were treading on thin ice legally. Meanwhile, Harriman was behind the scenes challenging the validity of the SPLA tax title. He met with Judge T. P. Hawley and persuaded him to declare Clark’s tax title as invalid, citing an obscure law that dealt with construction in Nevada by out-of-state companies. He contended that the Utah & California Company had committed fraud and convinced the judge to rule in his favor. He prevailed and on April 24, 1901, General Land Office officials in Washington reversed the decision of Nevada officials in Carson City which issued Clark’s permits. The Utah & California was blocked and the Short Line, who held prior rights, took control of the NP and the Utah & Pacific grades. On April 27, Harriman obtained an injunction which blocked Clark from interfering with the OSL construction in Clover Creek canyon. There was a little known law which prevented a railroad from monopolizing mountain passes and canyons, so Harriman could now build a line parallel to Clark’s in the canyon. Position was critical and they were both concerned over who would get the best grades in the narrow canyon. Clark didn’t rest and moved in a different direction, buying the tax title to the grade from Pioche to Clover Valley junction, and from there to Uvada. Because Clark couldn’t build in Clover Creek canyon he moved his camp to Meadow Valley wash.

The Utah, Nevada & California, a subsidiary of the OSL, was tasked with building the road from Uvada to the California state line through Meadow Valley wash to Moapa to Las Vegas, then south over Timber Mountain and Ash Mountain Pass to the California/Nevada state line. They would then cross the Santa Fe line at Ludlow and connect with the Southern Pacific at Beaumont over Morongo Pass.

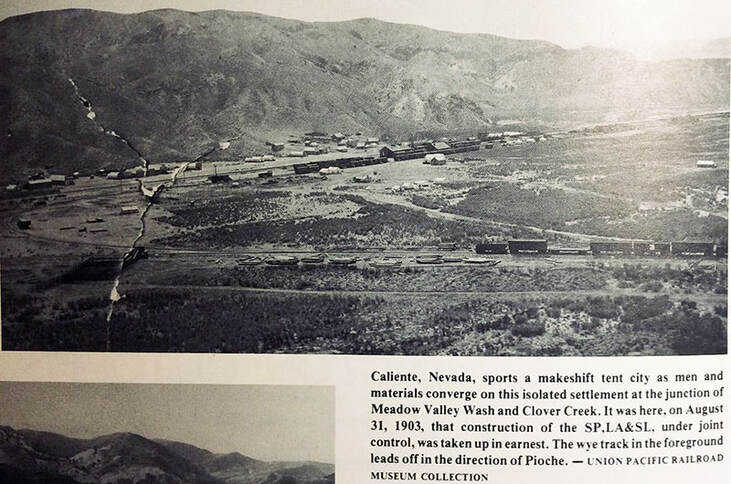

Things were heating up as the SPLA crews erected a wire fence barricade at Caliente to stop the OSL from building south from that point. The OSL crews tore down the barricade and overwhelmed the 3 guards left there to defend it. Shots were fired and conflicting reports emerged concerning the outcome, from no strife at all to an all out battle in which several men lost their lives.

Shortly thereafter, Clark appealed his case and Judge Hawley reversed the decision against the SPLA and now they could lay claim to all the OSL track through Lincoln County, Nevada. The OSL was now effectively blocked from building south from Caliente. There were rumors that the two companies would cooperate in the completion of the road. They met on September 13, 1901 in Salt Lake City to work out a compromise. Engineers from both camps took to the field to find suitable locations for lines for each railroad. Also at issue were the original surveys. If they built the lines following the surveys they would intersect 26 times in 60 miles.

Meanwhile, both railroads were anxious to get started. Clark sent engineer H. M. McCartney to survey from Caliente to Moapa, ending up in Las Vegas. At the same time, not wanting to be outdone, Harriman gave orders that he wanted the OSL line into Los Angeles to be completed by January 1, 1903.

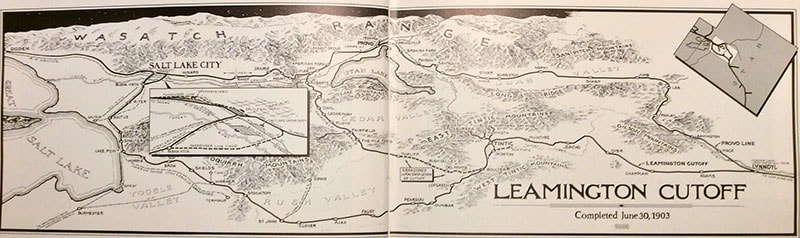

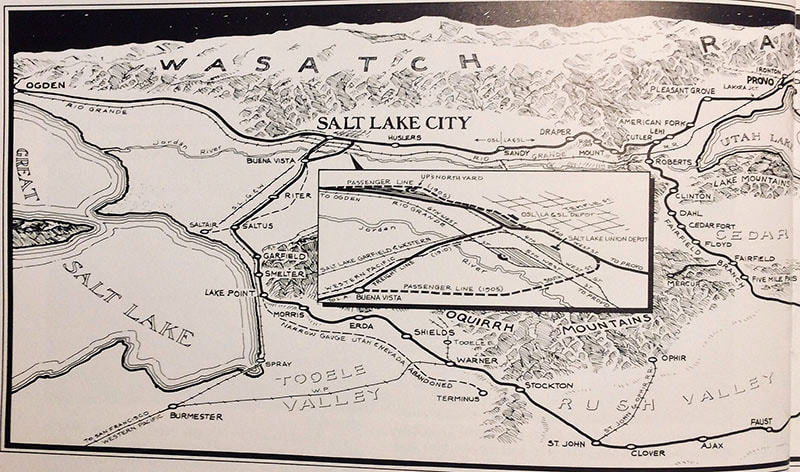

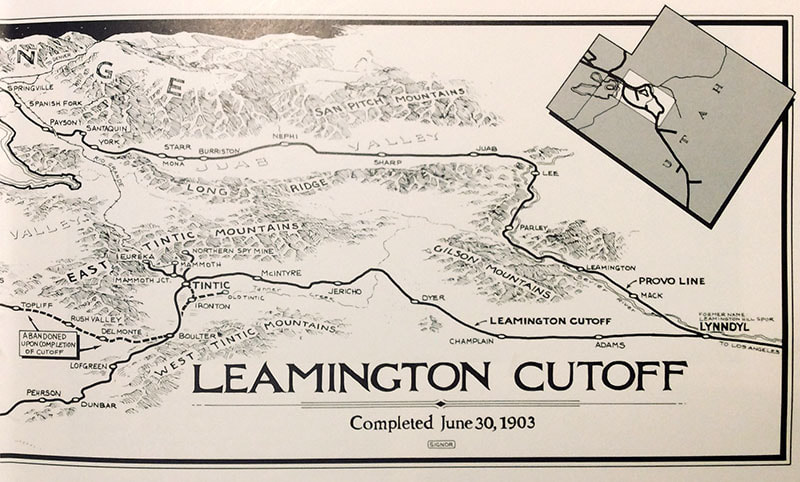

Switching stories a little, I will jump from Nevada to the old OSL main line from Salt Lake through Provo, then south and west through the Juab valley. The route had troublesome curvatures and grades that the SPLA wanted to change. Vice President Gibbon announced that the SPLA would build a new line from Salt Lake west to the Great Salt Lake shoreline, then south along the western slopes of the Oquirrh Mountains through Tooele and Rush Valleys, passing the old Salt Lake & Western Line at Boulter, then connecting with the old main line at Lynndyl where it came from the east through Leamington.

But shortly after this plan was announced, the OSL forged ahead and stole the show by starting construction on their own line along this same route. This new line came to be known as the Leamington Cutoff and was completed June 30, 1903.

But despite the OSL’s activities, J. Ross Clark in Los Angeles made it known that the SPLA would still go ahead with their plans to build a railroad from Salt Lake to Southern California. One plan, which caused some controversy, was to build a line over Cajon Pass below the Santa Fe grade which was already there. The battle for the canyons ended in a draw.

Things were heating up as the SPLA crews erected a wire fence barricade at Caliente to stop the OSL from building south from that point. The OSL crews tore down the barricade and overwhelmed the 3 guards left there to defend it. Shots were fired and conflicting reports emerged concerning the outcome, from no strife at all to an all out battle in which several men lost their lives.

Shortly thereafter, Clark appealed his case and Judge Hawley reversed the decision against the SPLA and now they could lay claim to all the OSL track through Lincoln County, Nevada. The OSL was now effectively blocked from building south from Caliente. There were rumors that the two companies would cooperate in the completion of the road. They met on September 13, 1901 in Salt Lake City to work out a compromise. Engineers from both camps took to the field to find suitable locations for lines for each railroad. Also at issue were the original surveys. If they built the lines following the surveys they would intersect 26 times in 60 miles.

Meanwhile, both railroads were anxious to get started. Clark sent engineer H. M. McCartney to survey from Caliente to Moapa, ending up in Las Vegas. At the same time, not wanting to be outdone, Harriman gave orders that he wanted the OSL line into Los Angeles to be completed by January 1, 1903.

Switching stories a little, I will jump from Nevada to the old OSL main line from Salt Lake through Provo, then south and west through the Juab valley. The route had troublesome curvatures and grades that the SPLA wanted to change. Vice President Gibbon announced that the SPLA would build a new line from Salt Lake west to the Great Salt Lake shoreline, then south along the western slopes of the Oquirrh Mountains through Tooele and Rush Valleys, passing the old Salt Lake & Western Line at Boulter, then connecting with the old main line at Lynndyl where it came from the east through Leamington.

But shortly after this plan was announced, the OSL forged ahead and stole the show by starting construction on their own line along this same route. This new line came to be known as the Leamington Cutoff and was completed June 30, 1903.

But despite the OSL’s activities, J. Ross Clark in Los Angeles made it known that the SPLA would still go ahead with their plans to build a railroad from Salt Lake to Southern California. One plan, which caused some controversy, was to build a line over Cajon Pass below the Santa Fe grade which was already there. The battle for the canyons ended in a draw.

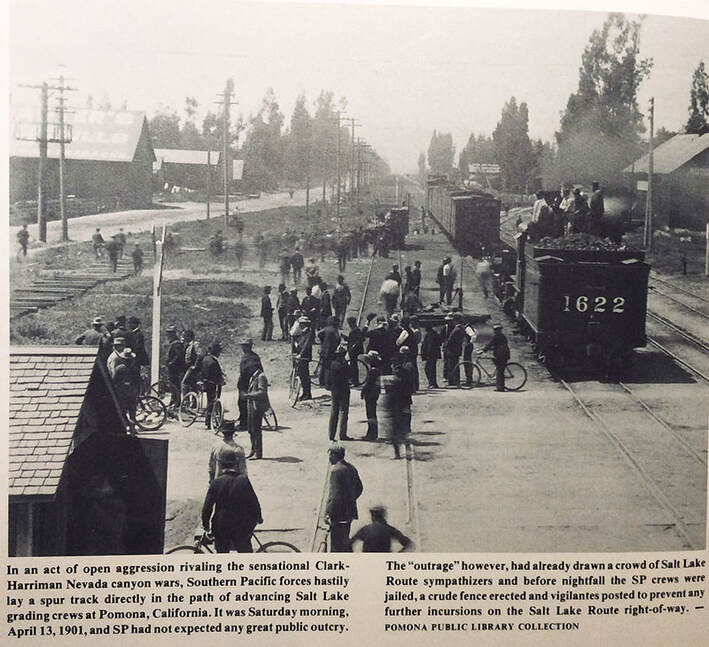

On the west coast, as work progressed on the Southern California branch from Hobart Station in San Pedro to Pomona, the situation got ugly. The Southern Pacific and the proposed line of the SPLA paralleled each other. On April 13, 1901, the SP built a siding along one block of 1st Street, crossing directly over the path of the SPLA’s right-of-way. News that the SP was attempting to interfere with the building of the SPLA line brought the city marshal and his deputies out in force to protect and hold the right-of-way against the encroachment by the SP crews. They resisted the order and an SP foreman and 50 Mexican workers were jailed. Another attempt by the SP to interfere with SPLA construction further west was blocked by vigilantes using a fire hose cart. By order of the marshal, the siding was torn up and a barb wire fence installed to stop the SP from any future harassment. When confronted, SP officials pretended to be totally ignorant of the incident. The matter was brought to court and the Pomona City council passed an ordinance giving the SPLA the right to occupy the street.

Construction progressed and by September 17, 1902, work commenced on grading the route to the east. As the summer of 1902 drew to a close, rumors began circulating about Senator Clark’s intentions concerning his railroad activities. Some made the claim that Clark would never get out of the Los Angeles basin. Others believed that Clark would connect with the Burlington in Wyoming. There was also a rumor that Senator Clark and E. H. Harriman had reached a compromise. As a matter of fact, since January of 1902, negotiations between T. E. Gibbon and J. Ross Clark representing the SPLA and Judge Kelly, general council for the OSL, representing Harriman had been taking place in New York City. On July 9, 1902, Clark and Harriman signed an agreement to merge and join forces to get the railroad built from Southern California to Salt Lake. On October 8, 1902, the agreement was formally announced.

Clark shrewdly recognized that operating two independent railroads between Los Angeles and Salt Lake would seriously affect profits. Harriman feared that the SPLA would merge with hostile forces, such as the Moffat Road, Burlington or Rock Island and threaten his empire. Another concern was that a Los Angeles to Salt Lake railroad in rival hands would take away business from the SP.

After the merger, all lawsuits were dismissed, deeds for all OSL lines south from Salt Lake City were transferred to the SPLA, all financial transactions were arranged and completed and a 99 year lease for joint use of the OSL’s Salt Lake yards was granted. Harriman made the announcement that construction would resume on July 8, 1903 with the goal of completing the line by early 1905. Part 4 will deal with the remaining short history of the ill-fated San Pedro Los Angeles & Salt Lake Railroad.

Construction progressed and by September 17, 1902, work commenced on grading the route to the east. As the summer of 1902 drew to a close, rumors began circulating about Senator Clark’s intentions concerning his railroad activities. Some made the claim that Clark would never get out of the Los Angeles basin. Others believed that Clark would connect with the Burlington in Wyoming. There was also a rumor that Senator Clark and E. H. Harriman had reached a compromise. As a matter of fact, since January of 1902, negotiations between T. E. Gibbon and J. Ross Clark representing the SPLA and Judge Kelly, general council for the OSL, representing Harriman had been taking place in New York City. On July 9, 1902, Clark and Harriman signed an agreement to merge and join forces to get the railroad built from Southern California to Salt Lake. On October 8, 1902, the agreement was formally announced.

Clark shrewdly recognized that operating two independent railroads between Los Angeles and Salt Lake would seriously affect profits. Harriman feared that the SPLA would merge with hostile forces, such as the Moffat Road, Burlington or Rock Island and threaten his empire. Another concern was that a Los Angeles to Salt Lake railroad in rival hands would take away business from the SP.

After the merger, all lawsuits were dismissed, deeds for all OSL lines south from Salt Lake City were transferred to the SPLA, all financial transactions were arranged and completed and a 99 year lease for joint use of the OSL’s Salt Lake yards was granted. Harriman made the announcement that construction would resume on July 8, 1903 with the goal of completing the line by early 1905. Part 4 will deal with the remaining short history of the ill-fated San Pedro Los Angeles & Salt Lake Railroad.