The Salt Lake Route Project: Part 4

In the 18 months between November 1901 and July 1903 the Oregon Short Line and Senator Clark’s company suspended construction on the new line through Nevada, but in California the San Pedro Salt Lake & Los Angeles RR continued to build from Los Angeles east to San Bernardino. With the compromise, Harriman would use his influence with the Southern Pacific and Santa Fe to secure joint use of trackage. Doing so would reduce the need for new construction and save time and money.

The Salt Lake Route obtained rights from the Southern Pacific from Riverside to Colton and San Bernardino with a 49-year lease for joint use of 9.8 miles of track that became effective June 18, 1903. The Santa Fe was more difficult to deal with, but by the summer of 1903 they negotiated joint use of 93.8 miles of Santa Fe track from Colton to Dagget, including the crucial line over Cajon pass. However, it wasn’t finalized until April 26, 1905, just 5 days before the Salt Lake Route officially opened for business. Terms were strict and the Santa Fe retained sole control of all facilities. The Salt Lake Route was to pay 60% of rates charged for passengers, freight and express or mail in return for the service provided.

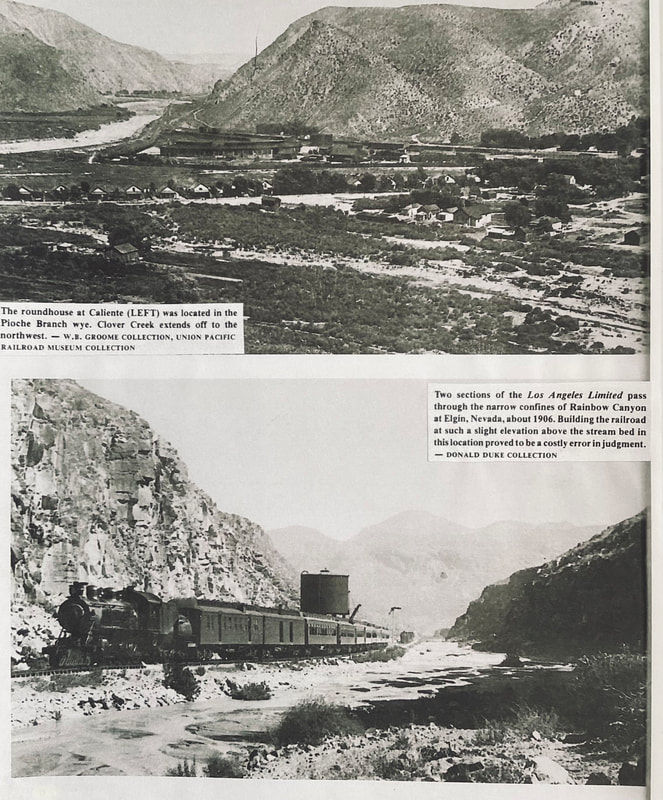

To hasten completion, construction commenced at both ends of the line. W.H. Bancroft, Vice President and General Manager of the OSL along with E.G. Tilton and R.E. Wells, Chief Engineer and General Manager of the SLR respectively would oversee construction from Caliente to Las Vegas. From Dagget to Las Vegas construction would be overseen by Chief Engineer Hawgood, formerly with the Los Angeles Terminal Railway. Construction under this joint control started August 31, 1903. Overnight, Caliente went from a peaceful village to what you would call a real wild west town with saloons, gambling houses and dance halls and the vice that accompanied them. Racial tensions arose as Greek, Syrian, Italian, Mexican and Japanese workers converged on the town. Fights and race riots broke out, but when all the trouble died down, 5 miles of track south of Caliente had been laid. On the southern end, the crews had built 30 miles of track from Dagget to the SF connection with 12 more miles of grade constructed beyond end of track. By the spring of 1904, they had advanced toward the Mojave River sink near Basin siding, then laid another 29 miles of track of 1% grade to Kelso. From there they installed 18 miles of 2.2% grade over a saddle between the Providence and Ivanpah Mountains. They were now within sight of the California/Nevada border and made camp at what is now present-day Cima.

Construction was progressing at a fast pace and by the end of April 1904, the 2 grading camps were only 40 miles apart while the track layers were separated by 130 miles. The first official party made a trip over the line at the end of May, with the entire line from Moapa to Caliente completed and ready for operation. Trains started running from Los Angeles to Riverside on March 12, 1904, and from San Bernardino and Riverside on the joint SP track on July 3. Despite blistering summer heat, with temperatures soaring to 120 degrees on the desert floor, the grade was completed to Las Vegas. From the south, 114 miles of track was laid from Dagget to Jean, Nevada by the end of 1904. The northern crews were held back by the need to construct tunnels to minimize the grade south of Las Vegas. By late 1904, the northern grading crews met the southern work gangs at Borax, south of Jean. The track layers were close behind and the work was rushed to completion.

Finally, on January 20, 1905, Chief Engineer Tilton wired Vice President W.H. Bancroft the following message: “Rails joined today between east and west ends of track at 3:15 PM at station G seventy-nine fifty-four.” The location was one mile from the siding at Sutor,

34 miles west of Las Vegas. The first car to cross the gap was the Harris track laying machine. No official ceremony was planned, but Mrs. R.E. Wells, wife of the General Manager, sent a gold-plated spike to the end of track which Tilton pushed into the last tie. The first train to pass over the new SLR was on February 9. Inspections revealed that additional work needed to be done on the right-of-way before full operation could commence and by mid-April Wells was satisfied that trains could roll. A special passenger train for the Woodmen of the World made the entire run from Salt Lake City to Los Angeles on April 15. Regular passenger service started the evening of May 1, 1905.

The train consisted of 10 cars: a baggage and express car, a chair car, 2-day coaches, 3 tourist sleepers, a diner, a standard sleeper and an observation car. The SLR was now officially open for business. Senator Clark envisioned the most modern railroad in the country, but with the rush to finish building the line he accepted lesser standards of construction. All main line trackage was intended to utilize 75 lb rail, but they settled for 60 lb rail to be replaced with the heavier rail as it became available from the steel mills.

The Salt Lake Route obtained rights from the Southern Pacific from Riverside to Colton and San Bernardino with a 49-year lease for joint use of 9.8 miles of track that became effective June 18, 1903. The Santa Fe was more difficult to deal with, but by the summer of 1903 they negotiated joint use of 93.8 miles of Santa Fe track from Colton to Dagget, including the crucial line over Cajon pass. However, it wasn’t finalized until April 26, 1905, just 5 days before the Salt Lake Route officially opened for business. Terms were strict and the Santa Fe retained sole control of all facilities. The Salt Lake Route was to pay 60% of rates charged for passengers, freight and express or mail in return for the service provided.

To hasten completion, construction commenced at both ends of the line. W.H. Bancroft, Vice President and General Manager of the OSL along with E.G. Tilton and R.E. Wells, Chief Engineer and General Manager of the SLR respectively would oversee construction from Caliente to Las Vegas. From Dagget to Las Vegas construction would be overseen by Chief Engineer Hawgood, formerly with the Los Angeles Terminal Railway. Construction under this joint control started August 31, 1903. Overnight, Caliente went from a peaceful village to what you would call a real wild west town with saloons, gambling houses and dance halls and the vice that accompanied them. Racial tensions arose as Greek, Syrian, Italian, Mexican and Japanese workers converged on the town. Fights and race riots broke out, but when all the trouble died down, 5 miles of track south of Caliente had been laid. On the southern end, the crews had built 30 miles of track from Dagget to the SF connection with 12 more miles of grade constructed beyond end of track. By the spring of 1904, they had advanced toward the Mojave River sink near Basin siding, then laid another 29 miles of track of 1% grade to Kelso. From there they installed 18 miles of 2.2% grade over a saddle between the Providence and Ivanpah Mountains. They were now within sight of the California/Nevada border and made camp at what is now present-day Cima.

Construction was progressing at a fast pace and by the end of April 1904, the 2 grading camps were only 40 miles apart while the track layers were separated by 130 miles. The first official party made a trip over the line at the end of May, with the entire line from Moapa to Caliente completed and ready for operation. Trains started running from Los Angeles to Riverside on March 12, 1904, and from San Bernardino and Riverside on the joint SP track on July 3. Despite blistering summer heat, with temperatures soaring to 120 degrees on the desert floor, the grade was completed to Las Vegas. From the south, 114 miles of track was laid from Dagget to Jean, Nevada by the end of 1904. The northern crews were held back by the need to construct tunnels to minimize the grade south of Las Vegas. By late 1904, the northern grading crews met the southern work gangs at Borax, south of Jean. The track layers were close behind and the work was rushed to completion.

Finally, on January 20, 1905, Chief Engineer Tilton wired Vice President W.H. Bancroft the following message: “Rails joined today between east and west ends of track at 3:15 PM at station G seventy-nine fifty-four.” The location was one mile from the siding at Sutor,

34 miles west of Las Vegas. The first car to cross the gap was the Harris track laying machine. No official ceremony was planned, but Mrs. R.E. Wells, wife of the General Manager, sent a gold-plated spike to the end of track which Tilton pushed into the last tie. The first train to pass over the new SLR was on February 9. Inspections revealed that additional work needed to be done on the right-of-way before full operation could commence and by mid-April Wells was satisfied that trains could roll. A special passenger train for the Woodmen of the World made the entire run from Salt Lake City to Los Angeles on April 15. Regular passenger service started the evening of May 1, 1905.

The train consisted of 10 cars: a baggage and express car, a chair car, 2-day coaches, 3 tourist sleepers, a diner, a standard sleeper and an observation car. The SLR was now officially open for business. Senator Clark envisioned the most modern railroad in the country, but with the rush to finish building the line he accepted lesser standards of construction. All main line trackage was intended to utilize 75 lb rail, but they settled for 60 lb rail to be replaced with the heavier rail as it became available from the steel mills.

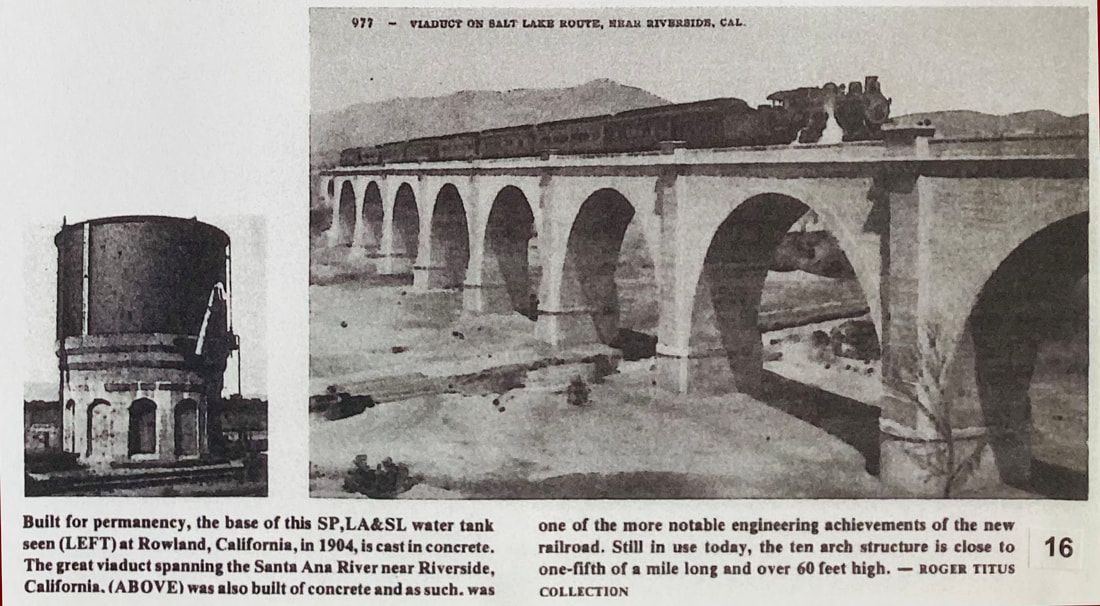

Some of the structures and buildings along the line were of high quality and unique. The great viaduct across the Santa Ana River was a 10 arch structure close to ⅕ mile long and 60 feet from the riverbed to the rails. At the time of its construction, it was the longest concrete arch bridge in the world. All standard water tanks were steel set on concrete pedestals. The railroad adopted a California mission style depot design and examples could be seen in Pomona, Ontario, Riverside, San Bernardino, Otis (Yermo), Kelso, Las Vegas, Caliente and Milford. The beautiful &400,000 depot in Salt Lake City was shared with the OSL and was built using a more traditional design with red sandstone and steel.

As for the rolling stock acquired, 8 locomotives came with the acquisition of the old Los Angeles Terminal: 2 Rhode Island 2-4-4 Ts built in 1889, 2 each of Baldwin 4-4-0’s and 4-6-0’s from 1891, a 1901 Schenectady 4-4-0, 2 new Schenectady 0-6-0’s, 2 Brooks 4-6-0’s and 4 more Schenectadys. As a result of the Harriman/Clark agreement, they added 19 locomotives from the OSL: 8 Baldwin and Grant 1887 4-4-0’s, 2 Lima Shays from 1902 and 7 Taunton 4-6-0’s dating back to 1882-1883. As construction progressed new locomotive purchases surged. In 1903 4 Pacific 4-6-2’s from Schenectady were added followed in 1904 by 6 more Baldwins and 9 heavy Consolidations. As the line opened up for service in 1905, 15 more Pacifics and 30 more Consolidations were bought. This new transcontinental railroad now had over 100 locomotives, 53 more locomotives joined the roster in 1907 of which there were 46 Consolidations provided by the Baldwin and Brooks locomotive works, 6 more Baldwin Pacifics and another Shay. Poor’s Manual also listed the SPLA&SL as owning 3,077 freight cars, 17 baggage, mail and express cars and 68 passenger cars as of June 30, 1905.

The pride of the new line was the deluxe flyer Los Angeles Limited. 8 new sets of trains were ordered from the Pullman Company. Each set consisted of one 14 section car with a drawing room, a standard sleeper, one tourist sleeper and a composite observation and

buffet car which could be converted to a diner. Of note about the 70-foot combination observation/buffet car. A 35-foot smoking/buffet section in the forward part was followed by a bar, cafe, library and observation salon. The main emphasis of the SLR passenger

department was the promotion of its passenger service. By 1909 there were 4 through trains with sleeper service between Chicago, St. Louis, Kansas City and Denver to Los Angeles and Pasadena. They were No’s. 1 and 2, the Overland Limited, and No’s. 7 and 8, the Los Angeles Limited. The Los Angeles Limited was operated in conjunction with the Chicago & Northwestern and the Union Pacific. The trains ran between Chicago and Los Angeles with an average speed of 32 mph and could cover the distance of 2,229 miles between 68 and 69 hours.

As for the rolling stock acquired, 8 locomotives came with the acquisition of the old Los Angeles Terminal: 2 Rhode Island 2-4-4 Ts built in 1889, 2 each of Baldwin 4-4-0’s and 4-6-0’s from 1891, a 1901 Schenectady 4-4-0, 2 new Schenectady 0-6-0’s, 2 Brooks 4-6-0’s and 4 more Schenectadys. As a result of the Harriman/Clark agreement, they added 19 locomotives from the OSL: 8 Baldwin and Grant 1887 4-4-0’s, 2 Lima Shays from 1902 and 7 Taunton 4-6-0’s dating back to 1882-1883. As construction progressed new locomotive purchases surged. In 1903 4 Pacific 4-6-2’s from Schenectady were added followed in 1904 by 6 more Baldwins and 9 heavy Consolidations. As the line opened up for service in 1905, 15 more Pacifics and 30 more Consolidations were bought. This new transcontinental railroad now had over 100 locomotives, 53 more locomotives joined the roster in 1907 of which there were 46 Consolidations provided by the Baldwin and Brooks locomotive works, 6 more Baldwin Pacifics and another Shay. Poor’s Manual also listed the SPLA&SL as owning 3,077 freight cars, 17 baggage, mail and express cars and 68 passenger cars as of June 30, 1905.

The pride of the new line was the deluxe flyer Los Angeles Limited. 8 new sets of trains were ordered from the Pullman Company. Each set consisted of one 14 section car with a drawing room, a standard sleeper, one tourist sleeper and a composite observation and

buffet car which could be converted to a diner. Of note about the 70-foot combination observation/buffet car. A 35-foot smoking/buffet section in the forward part was followed by a bar, cafe, library and observation salon. The main emphasis of the SLR passenger

department was the promotion of its passenger service. By 1909 there were 4 through trains with sleeper service between Chicago, St. Louis, Kansas City and Denver to Los Angeles and Pasadena. They were No’s. 1 and 2, the Overland Limited, and No’s. 7 and 8, the Los Angeles Limited. The Los Angeles Limited was operated in conjunction with the Chicago & Northwestern and the Union Pacific. The trains ran between Chicago and Los Angeles with an average speed of 32 mph and could cover the distance of 2,229 miles between 68 and 69 hours.

Las Vegas

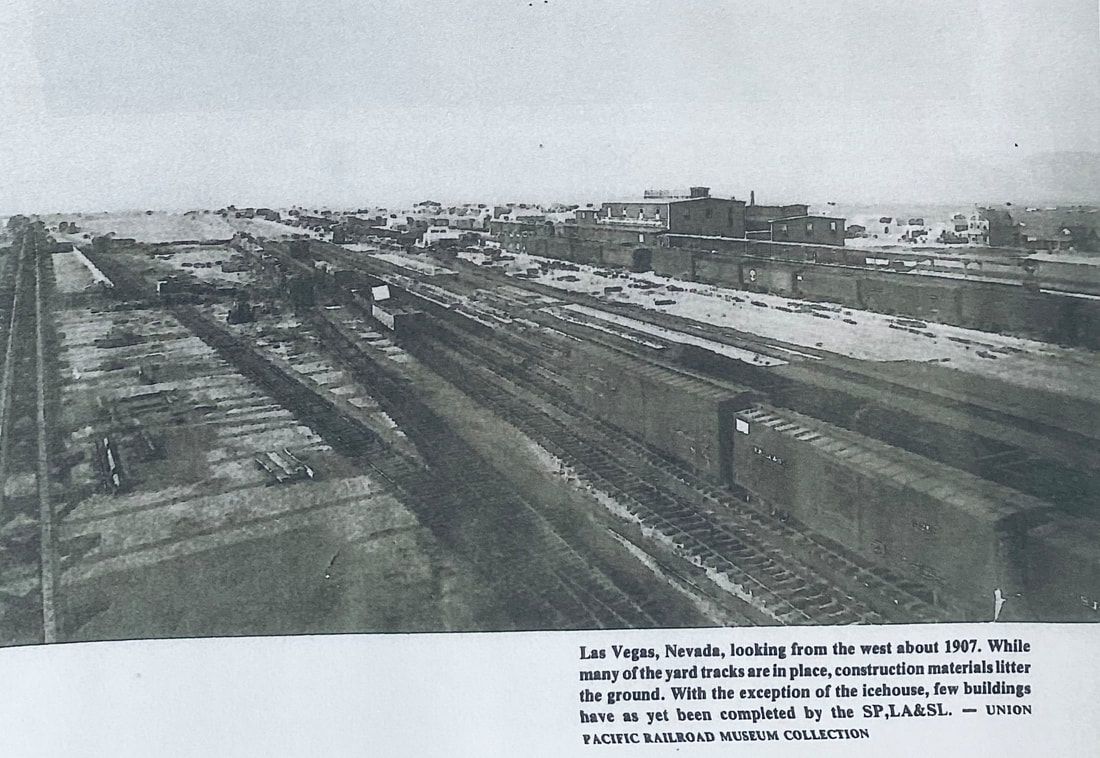

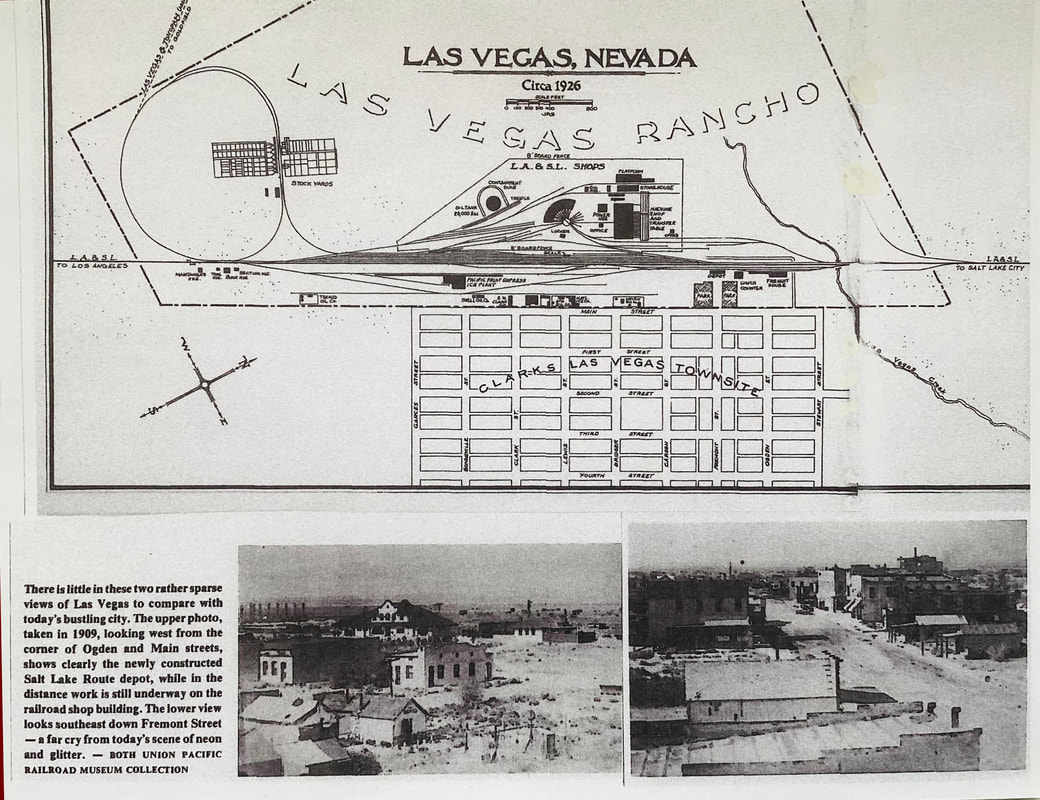

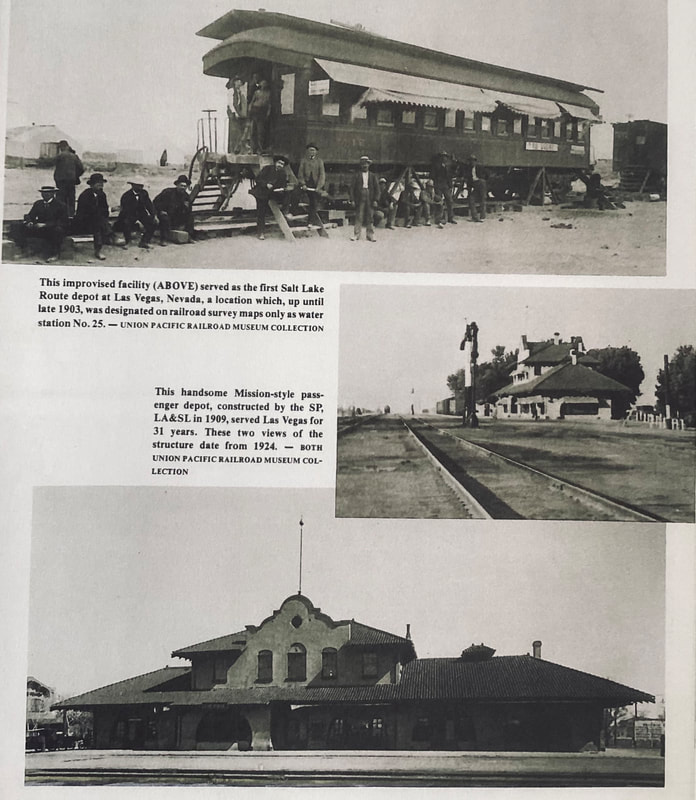

When the railroad arrived in the arid, barren Las Vegas Valley in 1900 there were 30 residents living in what was then known as the Las Vegas rancho. In 1855 Mormon pioneers settled there because of an abundant water supply but left 3 years later when Brigham Young recalled all the members back to Utah. In October 1902, Clark purchased the rancho from Helen Stewart, widow of a Gold Rush Forty-Niner, for $55,000 with plans to develop the site. By 1905 he had chosen the site to be a division point and predicted: “In a year from now we shall have churches and schools, and the tents of settlements will have given way to substantial buildings for business purposes and places of permanent abode.” In May 1905 they auctioned off 1,200 lots. A new depot was erected in early 1909, and by summer a large machine shop was built. Company residences were constructed of concrete and a model town sprang up in the desert the likes of Pullman, Illinois. Las Vegas was another example of the SLR’s aggressive development of unsettled land along the route. Delta, Utah and the surrounding area were another result of the railroad’s promotion of land development.

When the railroad arrived in the arid, barren Las Vegas Valley in 1900 there were 30 residents living in what was then known as the Las Vegas rancho. In 1855 Mormon pioneers settled there because of an abundant water supply but left 3 years later when Brigham Young recalled all the members back to Utah. In October 1902, Clark purchased the rancho from Helen Stewart, widow of a Gold Rush Forty-Niner, for $55,000 with plans to develop the site. By 1905 he had chosen the site to be a division point and predicted: “In a year from now we shall have churches and schools, and the tents of settlements will have given way to substantial buildings for business purposes and places of permanent abode.” In May 1905 they auctioned off 1,200 lots. A new depot was erected in early 1909, and by summer a large machine shop was built. Company residences were constructed of concrete and a model town sprang up in the desert the likes of Pullman, Illinois. Las Vegas was another example of the SLR’s aggressive development of unsettled land along the route. Delta, Utah and the surrounding area were another result of the railroad’s promotion of land development.

The main emphasis, though, was the promotion of Southern California. The availability of rail service allowed other lines and spurs to be built to service surrounding mining operations. The line ran along the south shore of the Great Salt Lake on the Leamington Cutoff past the Utah Copper Company’s smelting and refining operations at Smelter Station and the Tooele Valley mines and mills. When I worked for

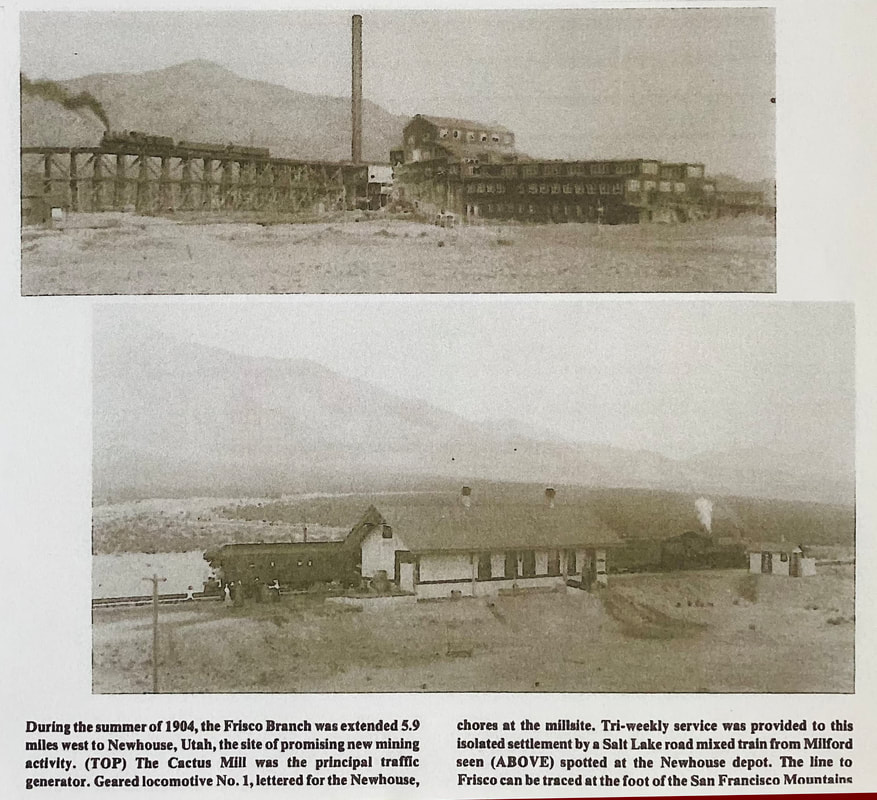

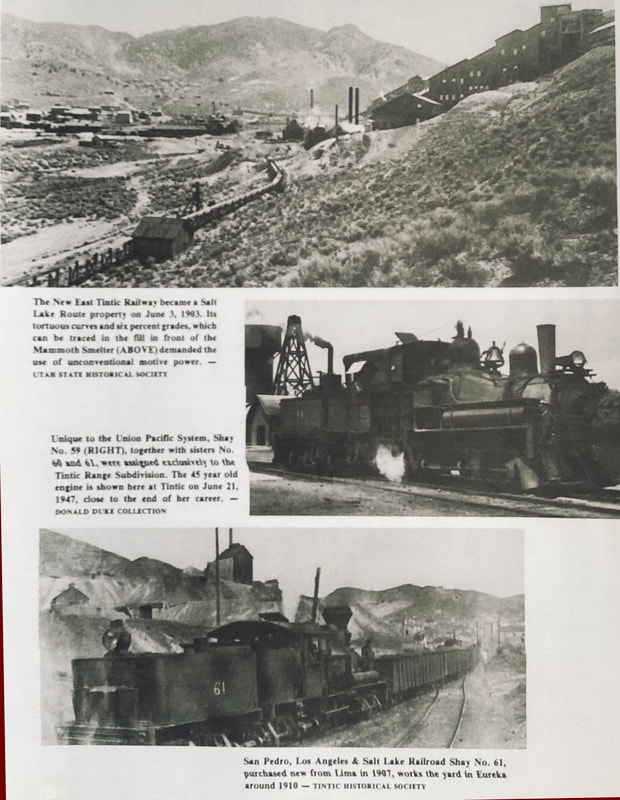

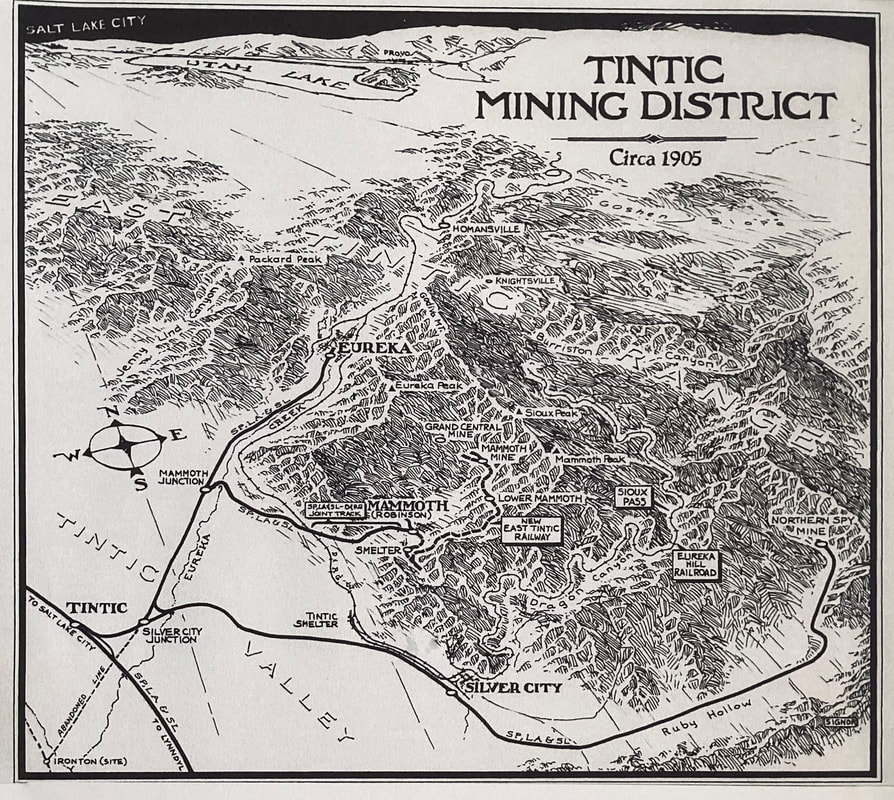

the Bingham & Garfield Railroad, the spur which connected the B&G to the main line was always known as the ‘Pedro spur. In June 1904 a 5.9-mile extension of the Frisco branch was built from Frisco to Newhouse to service the Cactus Mine. The Tintic mining district was one of the greatest and most successful operations in Utah and in 1959, surpassed California’s Mother Lode district in gold production. It was located 55 miles south of Salt Lake City and was 5 miles wide by 15 miles long. There were 4 railroads operating between Knightsville and Diamond - the Salt Lake & Western (which was combined with the OSL) and the Rio Grande Western, who shared track with the OSL, the Eureka Hill Railway and the New East Tintic Railway During the Harriman/Clark merger the New East Tintic Railway was being considered for inclusion in the new railroad and was accomplished on July 6, 1903. An abandoned grade of the UP into Pioche was revived in February 1907. The Caliente & Pioche Railroad was incorporated on June 6, 1906, and work commenced on rebuilding the line. As Clark had organized and financed the branch, it was leased to the SPLA&SL on January 1, 1908 and acquired by them in March.

the Bingham & Garfield Railroad, the spur which connected the B&G to the main line was always known as the ‘Pedro spur. In June 1904 a 5.9-mile extension of the Frisco branch was built from Frisco to Newhouse to service the Cactus Mine. The Tintic mining district was one of the greatest and most successful operations in Utah and in 1959, surpassed California’s Mother Lode district in gold production. It was located 55 miles south of Salt Lake City and was 5 miles wide by 15 miles long. There were 4 railroads operating between Knightsville and Diamond - the Salt Lake & Western (which was combined with the OSL) and the Rio Grande Western, who shared track with the OSL, the Eureka Hill Railway and the New East Tintic Railway During the Harriman/Clark merger the New East Tintic Railway was being considered for inclusion in the new railroad and was accomplished on July 6, 1903. An abandoned grade of the UP into Pioche was revived in February 1907. The Caliente & Pioche Railroad was incorporated on June 6, 1906, and work commenced on rebuilding the line. As Clark had organized and financed the branch, it was leased to the SPLA&SL on January 1, 1908 and acquired by them in March.

The Panic, The Breakup & The Flood

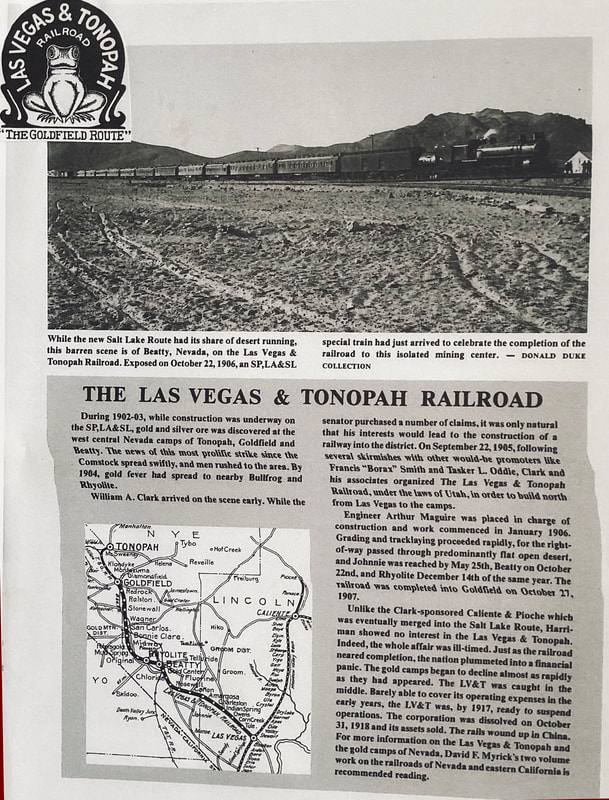

Disaster struck on three fronts in 1907. A major panic and recession hit and Wall Street and Southern Nevada felt the pain. More than a dozen mining camps were abandoned and became ghost towns almost overnight. Senator Clark was heavily invested in the Caliente & Pioche and the Las Vegas & Tonopah, relying on the ore shipments to operate.

Then, if that wasn’t enough, the divestment of Harriman’s empire started. The United States District Attorney for the state for Utah, under the direction of Attorney General Charles J. Bonaparte, filed suit in the United States Circuit Court on February 18, 1908, to break up the Union Pacific empire. The District Attorney also sought to divest the UP of its holdings in competing railroads, including the SPLA&SL. The hearings lasted until 1910 and by that time Harriman had died and the UP had already sold its interests in other lines, including the Santa Fe, Great Northern and Northern Pacific. In 1911 the Circuit Court decided in favor of the UP-retaining control of the SP, but the decision was reversed on December 2, 1912, which separated the two railroads. The Up, however, was allowed to retain ownership of the San Pedro line but 4 years of uncertainty shook the operations and capital spending to the core.

Disaster struck on three fronts in 1907. A major panic and recession hit and Wall Street and Southern Nevada felt the pain. More than a dozen mining camps were abandoned and became ghost towns almost overnight. Senator Clark was heavily invested in the Caliente & Pioche and the Las Vegas & Tonopah, relying on the ore shipments to operate.

Then, if that wasn’t enough, the divestment of Harriman’s empire started. The United States District Attorney for the state for Utah, under the direction of Attorney General Charles J. Bonaparte, filed suit in the United States Circuit Court on February 18, 1908, to break up the Union Pacific empire. The District Attorney also sought to divest the UP of its holdings in competing railroads, including the SPLA&SL. The hearings lasted until 1910 and by that time Harriman had died and the UP had already sold its interests in other lines, including the Santa Fe, Great Northern and Northern Pacific. In 1911 the Circuit Court decided in favor of the UP-retaining control of the SP, but the decision was reversed on December 2, 1912, which separated the two railroads. The Up, however, was allowed to retain ownership of the San Pedro line but 4 years of uncertainty shook the operations and capital spending to the core.

There was very little resistance to flooding in the narrow canyons and passes along the route, so surface ditches were essential. In some places the cost of building the ditches exceeded the cost of the railroad. The engineers located the grades high enough above the stream bed to avoid flooding, or so they thought. There was minor flooding in 1905 but not enough to cause problems or damage. In March 1906 a single storm dropped enough water that in Meadow Valley Wash it rose between 5 and 10 feet in places and took out whole sections of track between Elgin and Hoya. Repairs were made and service started again after 3 weeks. They built dikes, riprap and other structures thinking this would prevent further damage.

But in February and March of 1907 major flooding occurred in Southern Nevada. The rain began to fall on February 22 and didn’t let up for 12 hours. It fell on the existing snowpack, rapidly melting the snow which combined into raging torrents racing down Clover and Caliente Creeks taking the railroad with it. Then on March 5, another steady rain fell on the Caliente area for 9 hours. The stream rose 10 to 15 feet, 3 feet above the February 22 storm, and flooded the town. When Chief Engineer Tilton surveyed the damage, there were over 100 washouts between Barclay, 19 miles east of Caliente, and to Guelph, 64 miles west of Caliente - a distance of 83 miles. The flood waters passed over or reached the bottoms of 27 bridges, washing out the banks under each bridge. They brought in William Hood, Chief Engineer of the Southern Pacific and an expert on western railroad construction and location, to assess the damage and offer a solution.

Despite the advice of E.G. Tilton and warnings from the local Paiute Indians for radical relocation, he chose to raise the grade 4 feet above the high-water mark of 1907 and install more damage control structures. They changed 6 river channels and built 8 new steel bridges along with the other extensive repairs. The final bill for the upgrade was in the neighborhood of $770,000. They got by safely for the next 2 years with minor flooding and no damage, but the worst was yet to come.

But in February and March of 1907 major flooding occurred in Southern Nevada. The rain began to fall on February 22 and didn’t let up for 12 hours. It fell on the existing snowpack, rapidly melting the snow which combined into raging torrents racing down Clover and Caliente Creeks taking the railroad with it. Then on March 5, another steady rain fell on the Caliente area for 9 hours. The stream rose 10 to 15 feet, 3 feet above the February 22 storm, and flooded the town. When Chief Engineer Tilton surveyed the damage, there were over 100 washouts between Barclay, 19 miles east of Caliente, and to Guelph, 64 miles west of Caliente - a distance of 83 miles. The flood waters passed over or reached the bottoms of 27 bridges, washing out the banks under each bridge. They brought in William Hood, Chief Engineer of the Southern Pacific and an expert on western railroad construction and location, to assess the damage and offer a solution.

Despite the advice of E.G. Tilton and warnings from the local Paiute Indians for radical relocation, he chose to raise the grade 4 feet above the high-water mark of 1907 and install more damage control structures. They changed 6 river channels and built 8 new steel bridges along with the other extensive repairs. The final bill for the upgrade was in the neighborhood of $770,000. They got by safely for the next 2 years with minor flooding and no damage, but the worst was yet to come.