The Salt Lake Project: Final Chapter

Or

The End of the San Pedro Los Angeles & Salt Lake RR

and the Los Angeles & Salt Lake RR

After the destruction of 1907 and over the following two years there were short periods of heavy rainfall but nothing that threatened railroad operations. But throughout the latter half of 1909 severe storms occurred affecting a three state area. Blizzards hampered

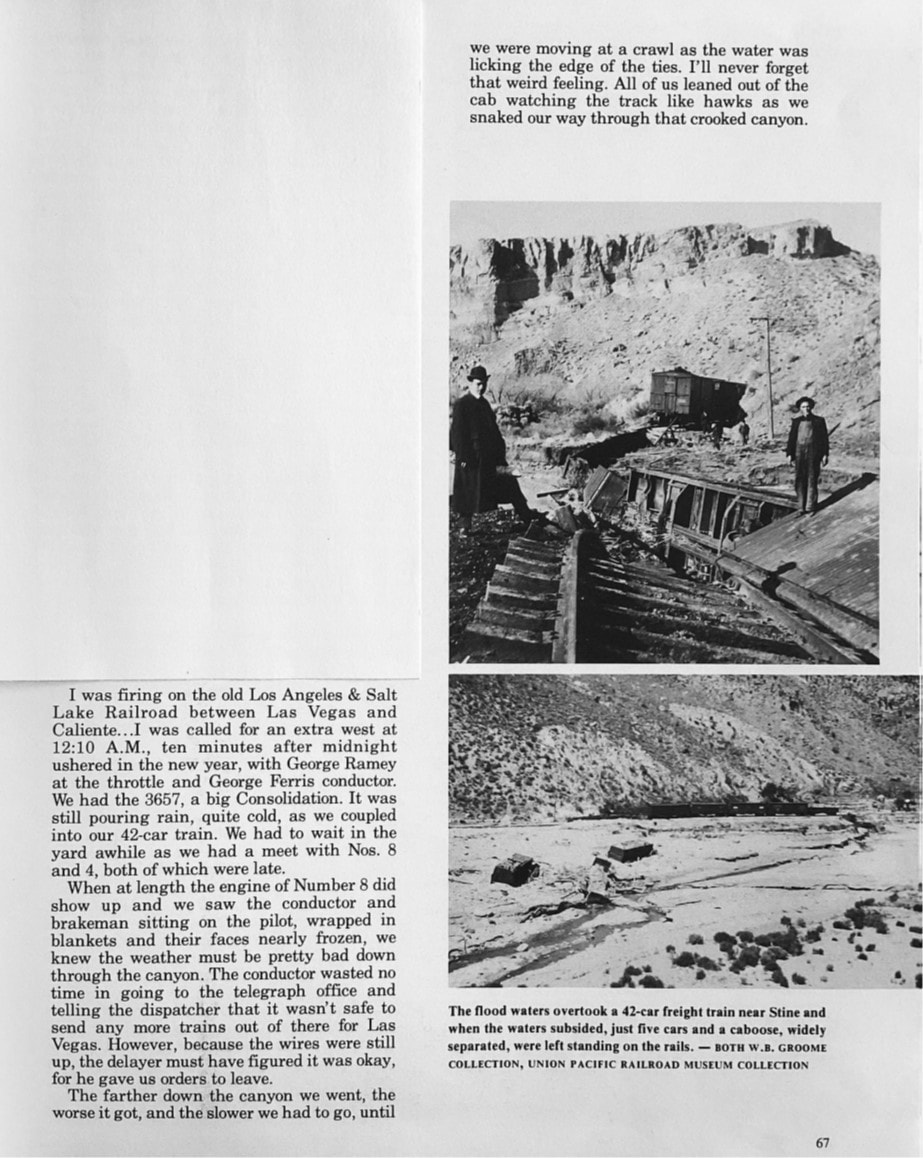

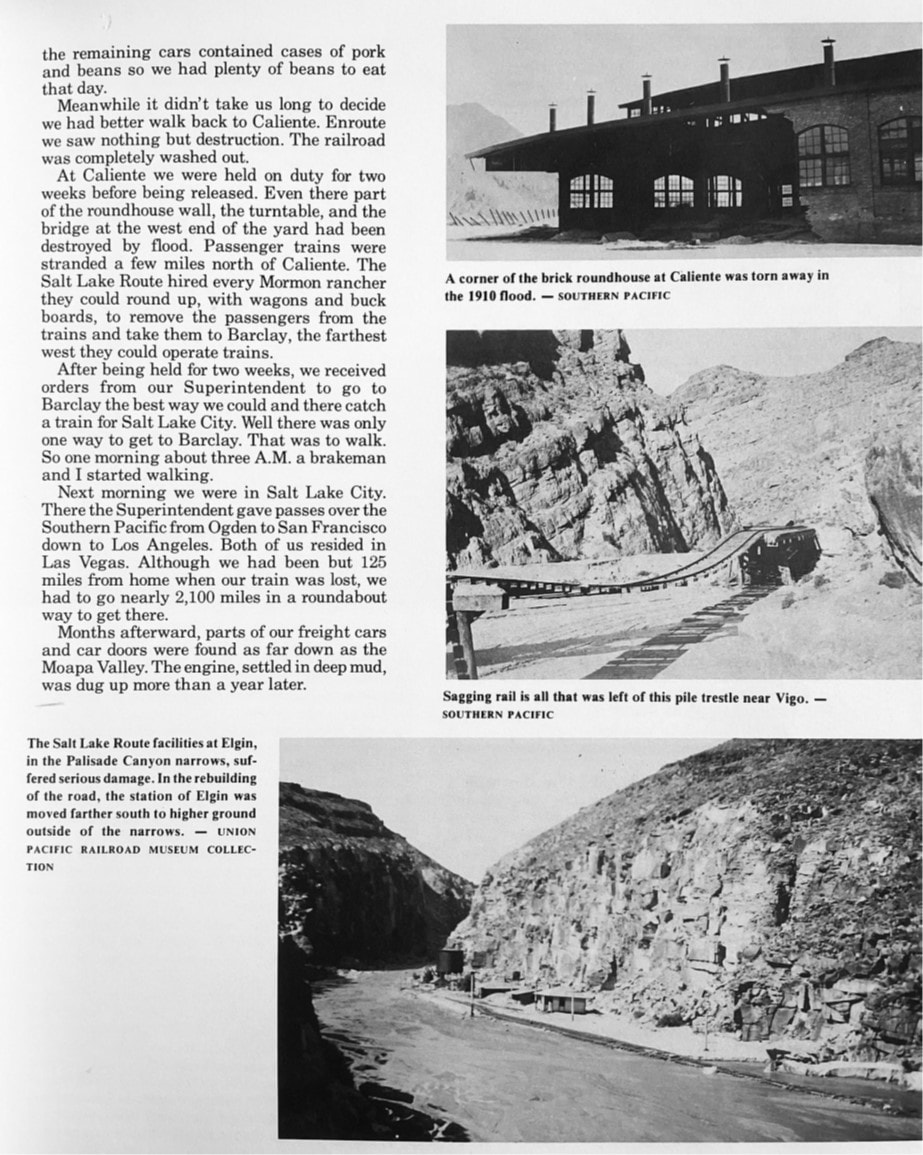

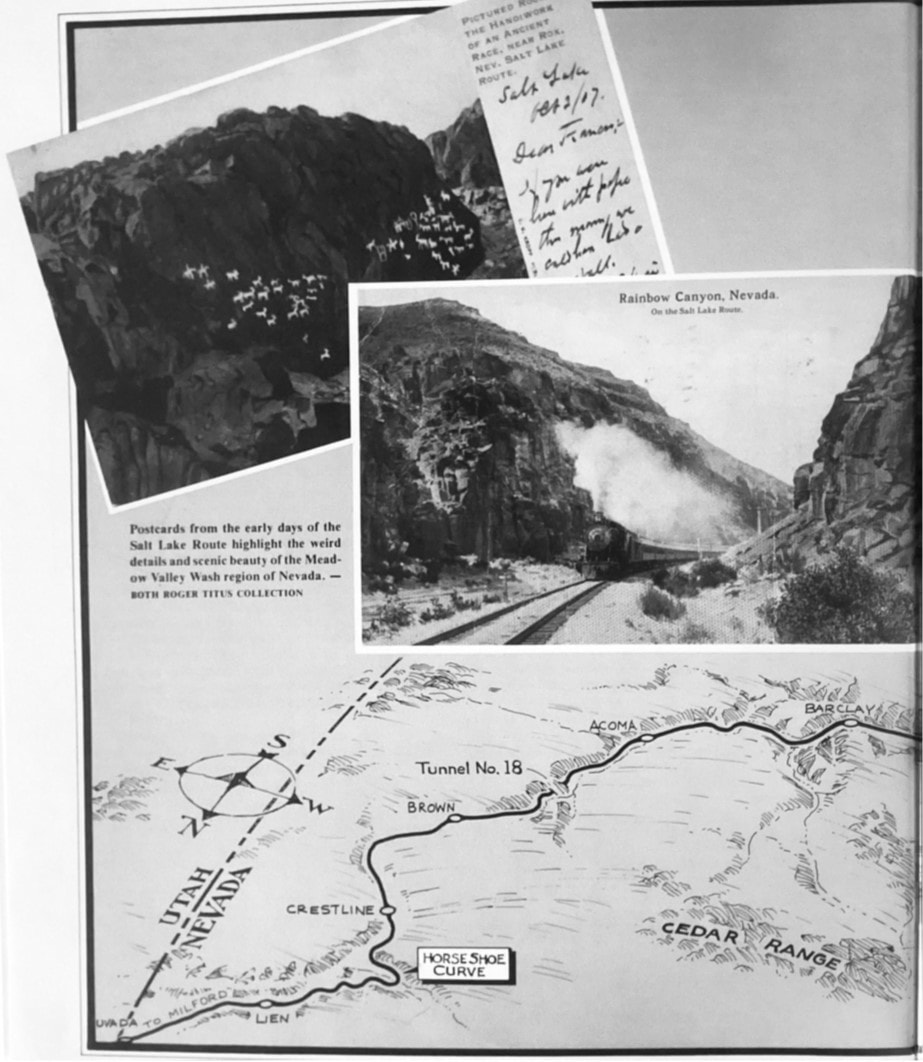

operations in southern Utah and Nevada and a disastrous scenario was unfolding. A heavy blanket of snow fell in upper Meadow Valley Wash and the Clover Creek areas just before Christmas. It laid down two feet at track level and much more higher up. On December 31 a warm rain moving up from the Gulf of California began to fall in southern Nevada. As the rain melted the snow and the ground already being saturated with water it rushed in tremendous torrents down the canyons with a volume five times that of 1907. Lou Martin, an eyewitness to the event tells his story:

operations in southern Utah and Nevada and a disastrous scenario was unfolding. A heavy blanket of snow fell in upper Meadow Valley Wash and the Clover Creek areas just before Christmas. It laid down two feet at track level and much more higher up. On December 31 a warm rain moving up from the Gulf of California began to fall in southern Nevada. As the rain melted the snow and the ground already being saturated with water it rushed in tremendous torrents down the canyons with a volume five times that of 1907. Lou Martin, an eyewitness to the event tells his story:

The news of the destruction and the condition of the road was slow in coming and was unknown for several days. Caliente and Pioche were cut off entirely and stranded for some time. The damage in Southern California was also serious over a wide area. The

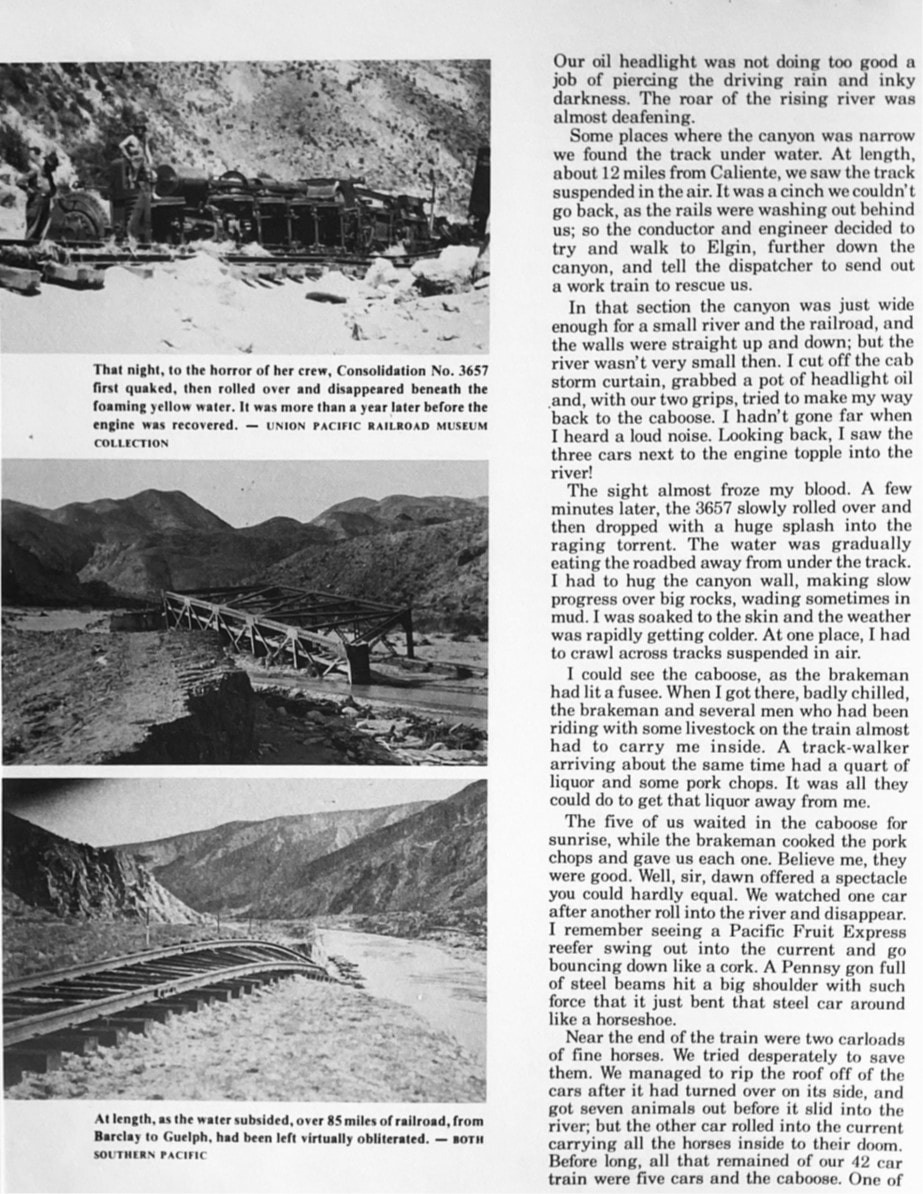

conditions along the San Gabriel and Mojave Rivers were to the extent that alternate routes and detours were used to continue operations. The only service north from Nevada was from Acoma near the state line to Salt Lake City. Chief engineer Tilton

arrived and left with a pack train to make a detailed examination and assessment of the damage. The railroad from Barclay to Guelph was almost totally obliterated with only two of the recently constructed steel bridges still intact. He found that the water had risen to eight feet above the 1907 level.

Valid reports of the destruction were slow in coming to the outside world. Some service was resumed on January 2, 1910, from Las Vegas to Los Angeles utilizing the detours around the damaged tracks and bridges, most notably the San Gabriel River Bridge at Pico. A twenty-mile-long lake formed along the Mojave River basin.

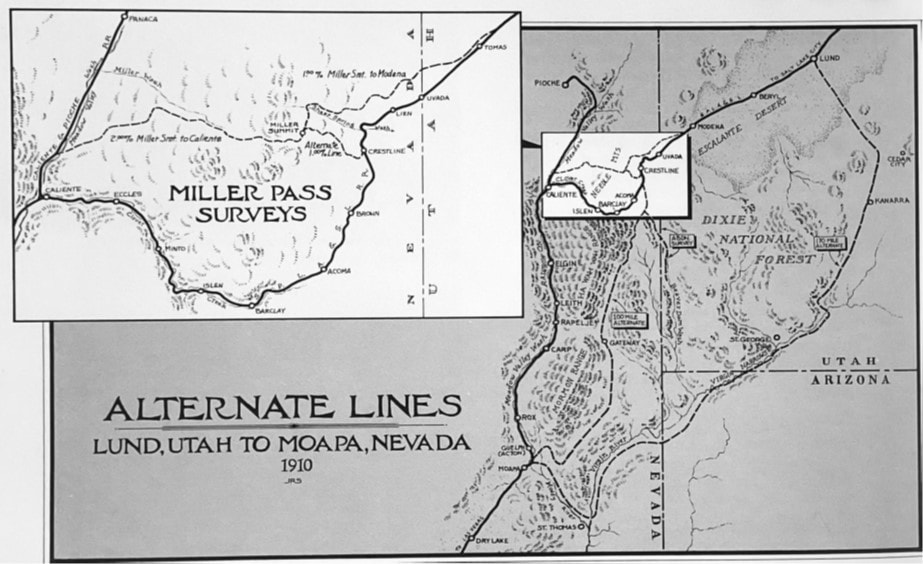

Many wondered what the Clarks would do after the hardships that they endured in the short life of their railroad, but most people had not considered who was really in control of the San Pedro Los Angeles & Salt Lake RR. With so much already invested in the railroad, E.H. Harriman decided immediately to rebuild. Realizing that they couldn’t safely build again in the lower elevations of the washes and canyons, they assigned William Hood to organize and head a committee to consider alternate routes. Three radical changes in the routes were decided on. While the committee was assessing the possibilities, W.H. Bancroft wired Hood and concluded “this flood has demonstrated that a line in that canyon (Meadow Valley Wash) couldn’t be built on any grade that would be feasible or practicable.”

Two of the three routes were passed on as being too costly and presented many of the same problems that plagued the existing line. The third line would be built from three miles west of Modena, Utah near the state line to a point three miles north of Caliente on

the Pioche branch through Miller Pass. The line would go west to Delamar, then south through the Pahranagat Valley to Dry Lake. But due to projected costs, they passed on that route as well. They eventually settled on a plan to build a carefully constructed “High

Line” above what remained of the line through Meadow Valley Wash.

conditions along the San Gabriel and Mojave Rivers were to the extent that alternate routes and detours were used to continue operations. The only service north from Nevada was from Acoma near the state line to Salt Lake City. Chief engineer Tilton

arrived and left with a pack train to make a detailed examination and assessment of the damage. The railroad from Barclay to Guelph was almost totally obliterated with only two of the recently constructed steel bridges still intact. He found that the water had risen to eight feet above the 1907 level.

Valid reports of the destruction were slow in coming to the outside world. Some service was resumed on January 2, 1910, from Las Vegas to Los Angeles utilizing the detours around the damaged tracks and bridges, most notably the San Gabriel River Bridge at Pico. A twenty-mile-long lake formed along the Mojave River basin.

Many wondered what the Clarks would do after the hardships that they endured in the short life of their railroad, but most people had not considered who was really in control of the San Pedro Los Angeles & Salt Lake RR. With so much already invested in the railroad, E.H. Harriman decided immediately to rebuild. Realizing that they couldn’t safely build again in the lower elevations of the washes and canyons, they assigned William Hood to organize and head a committee to consider alternate routes. Three radical changes in the routes were decided on. While the committee was assessing the possibilities, W.H. Bancroft wired Hood and concluded “this flood has demonstrated that a line in that canyon (Meadow Valley Wash) couldn’t be built on any grade that would be feasible or practicable.”

Two of the three routes were passed on as being too costly and presented many of the same problems that plagued the existing line. The third line would be built from three miles west of Modena, Utah near the state line to a point three miles north of Caliente on

the Pioche branch through Miller Pass. The line would go west to Delamar, then south through the Pahranagat Valley to Dry Lake. But due to projected costs, they passed on that route as well. They eventually settled on a plan to build a carefully constructed “High

Line” above what remained of the line through Meadow Valley Wash.

Due to pressure from the east, on March 10, 1910, it was decided that a temporary line would be built through the washed-out district so service could resume. It opened for through traffic on June 15, 1910.

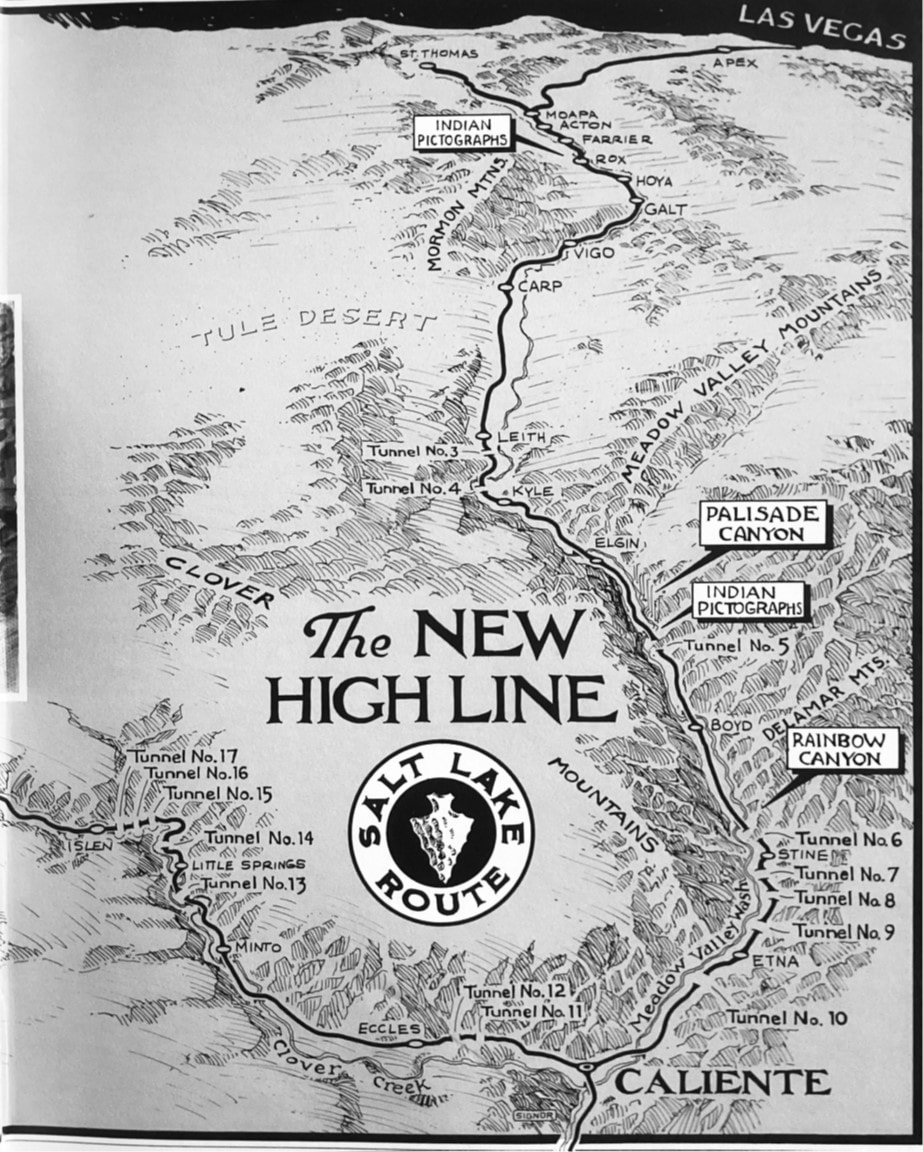

This new High Line would be built eight to twelve feet above the 1910 flood level. On August 23, 1910, contracts were awarded to the Utah Construction and the Shattuck-Edinger Companies to build the new road from Caliente to Guelph (now Acton), a distance of over 65 miles. Of that project only 6.12 miles of original track would be utilized. The High Line was finished in April 1912.

From January 1910 to mid 1912 the SPLA&SL was quietly working in other sections to build branch lines and spurs into promising new districts. Beginning in 1912, a 26-mile line was started from where Meadow Valley Wash enters the Muddy River past St.Thomas and Overton to its confluence with the Colorado River, southeast through the Moapa Valley and fertile farmlands to the rim of the Grand Canyon where Senator Clark

was planning to build a grand hotel for no less than $250,000. The line was officially opened on June 7, 1912.

This new High Line would be built eight to twelve feet above the 1910 flood level. On August 23, 1910, contracts were awarded to the Utah Construction and the Shattuck-Edinger Companies to build the new road from Caliente to Guelph (now Acton), a distance of over 65 miles. Of that project only 6.12 miles of original track would be utilized. The High Line was finished in April 1912.

From January 1910 to mid 1912 the SPLA&SL was quietly working in other sections to build branch lines and spurs into promising new districts. Beginning in 1912, a 26-mile line was started from where Meadow Valley Wash enters the Muddy River past St.Thomas and Overton to its confluence with the Colorado River, southeast through the Moapa Valley and fertile farmlands to the rim of the Grand Canyon where Senator Clark

was planning to build a grand hotel for no less than $250,000. The line was officially opened on June 7, 1912.

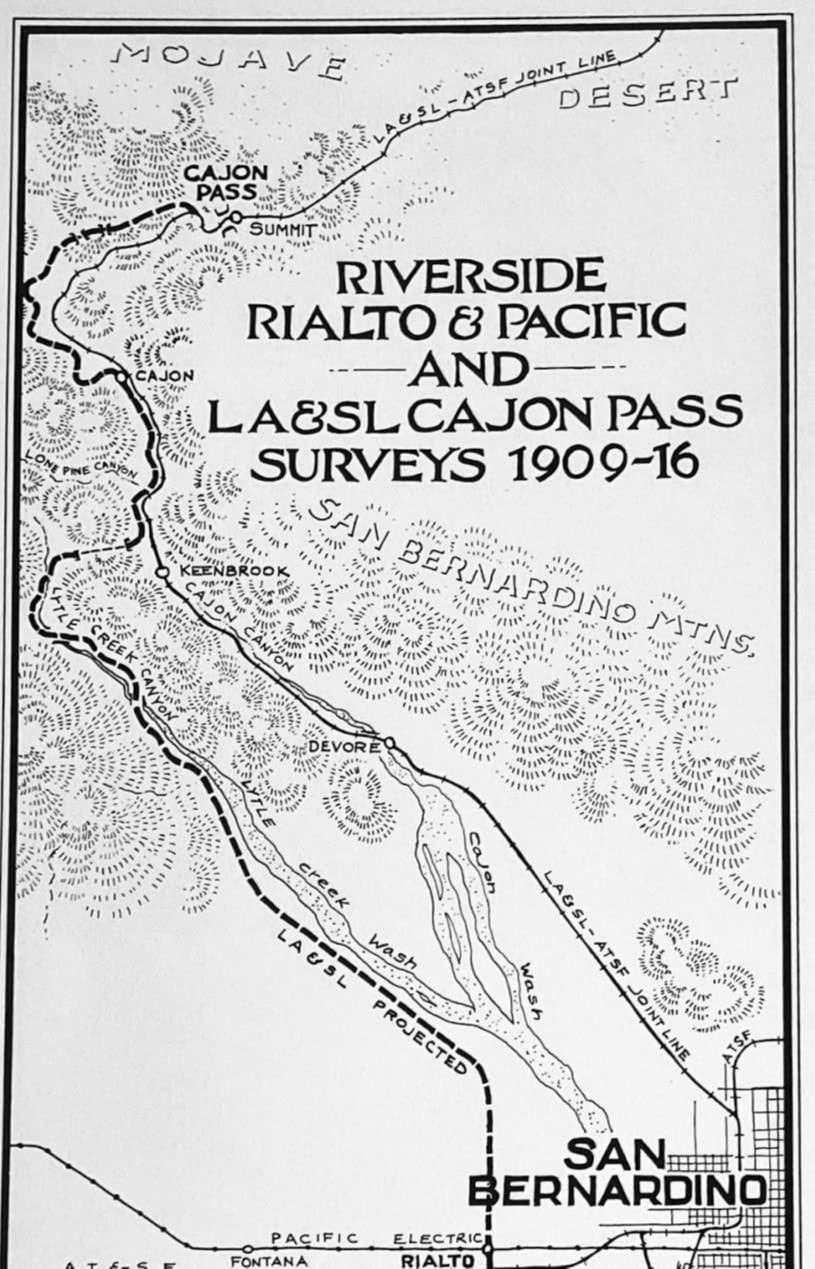

On October 1, 1915, the Delta branch was completed which ran 13.3 miles northwest to Sugarville and Lucerne. In Southern California, branch lines were built to the Blye quarries near Crestmore to service the Riverside Portland Cement Company. Also, at this

time, the situation with the Santa Fe joint track usage agreement through Cajon Pass became intolerable. According to the agreement, the Santa Fe trains had priority for their trains through the pass resulting in aggravating delays for the SPLA&SL runs. The crush

of traffic on the Santa Fe lines through the pass led to the construction of several sections of second track. The first two miles from San Bernardino was in place by 1910. At the same time track was being laid from Barstow to Hicks (now Cottonwood). By 1912

the second line on the west slope reached Keenbrook. The following year a second track was extended to Cajon Pass and an entirely new line was built on a 2.2% grade from Cajon to Summit.

The Salt Lake Route brought its grievances against the Santa Fe to an I.C.C panel in 1915, and on January 16, 1916, the board drew up a new contract granting the SPLA equal usage of the joint track and the 60% tariff they were paying the SF for online business was abolished. It was finalized on February 1, 1916, and was to be effective for 99 years.

In 1916 another branch was started from Pico to Santa Ana but was interrupted due to the First World War. Also in 1916, an important change to the corporate title of the SPLA&SL took place. The city of San Pedro had been annexed by the city of Los Angeles

in 1909 and thus had no further significance. On August 16, 1916, the company’s official name changed, and it became the Los Angeles & Salt Lake RR Company.

With the threat of war present for several years, things still remained business as usual. But with the sinking of the Lusitania in 1917, the United States entered the war by declaring war on Germany. On December 28, 1917, the Federal Government took control of the nation’s railroads through the formation of the United States Railroad Administration. The SLR had little involvement or importance where the war was concerned and were more or less left unchanged. Due to the turmoil of the war, the use of different railroad properties became more liberal. The yards and roundhouses at Barstow, San Bernardino and Colton were used freely by both roads.

Even though the armistice was signed on November 11, 1918, the government didn’t return the railroads to their owners until March 1, 1920. The two years and three-month period of federal control did little damage to the LA&SL compared to other carriers, but

the Clark’s were losing interest in their half-ownership of the road. Senator W.A. Clark and his brother J. Ross Clark dominated the early management of the SLR, but after 1913 Senator Clark vigorously pursued other interests although he continued as president.

Perhaps he lost interest in his railroad because of the disasters and losses, or the loss of J. Ross Clark’s son on the Titanic.

This lack of interest was especially annoying to the Union Pacific. Six days after regaining control of the Los Angeles & Salt Lake from the government, plans were made to expand and speed up the railroad’s passenger service. Construction that was put on hold because of the war resumed. But the Clark’s, who still held 50% ownership, balked at coming up with their share of the funds to proceed. It was becoming more difficult to get the Clark’s to even spend enough money just for maintenance to help keep the property in safe condition. The UP was committed to the business of running a railroad and couldn’t abide the current situation much longer.

On April 27, 1921, an agreement was negotiated with W.A. Clark and his associates that would allow the Union Pacific to purchase the remaining half of the capital in the Los Angeles & Salt Lake RR for $2,500,000 in cash and s$29,511,000 in Union Pacific and

Southern Pacific mortgage bonds. Thus, the UP and the Oregon Short Line became joint owners of the LA&SL Company and drew up plans to develop the SLR to its full potential.

Summary

Senator Clark and his associates took a great risk to invest in the Salt Lake Route and see it through. There were many who called them wild speculators to embark on a project through vast areas of barren country. But the project had been carefully planned with an

eye to the future and the potential for great profits that could be reaped. Sadly, the profits hoped for didn’t materialize during the period that the Clark’s were connected with the railroad. Just after the Clark’s pulled out, the Salt Lake Route began a period of

tremendous growth.

Long after the Clark’s left the scene, the corporate title of the Los Angeles & Salt Lake Railroad Company remained and continued to be used for years to come. But after April 27, 1921, the Union Pacific had as much importance in Los Angeles as it did in Omaha.

Judge Robert S. Lovett, chairman of the executive committee of the Union Pacific System, made the following announcement in regard to the change in control:

“The logical and natural destiny of the Los Angeles & Salt Lake ultimately as a railroad property is as a part of the Union Pacific System; and appreciation of this and not any differences led to the sale. It is a rather remarkable fact that during the 18 years of equal joint ownership and control by Senator Clark and us absolutely no disagreements respecting policies, control or management have ever arisen between us. Our relations could not have been more co-operative and harmonious.”

The term Salt Lake Route slowly disappeared as time went on. Once the Clark group was out, the LA&SL was free to undergo the same vigorous development that was a trademark of Union Pacific properties in the west. Between January 1922 and January

1925, the UP spent more than twelve million dollars on betterments and new construction, including replacing all light tracks with 90-pound rail.

The following page is a reprint of an article by Jeff Oaks on the SLR, OSL & UP that was published in the Winter 2000 issue of the NN and adds additional information about the merging of the railroads:

The Nails

The name Salt Lake Route can refer to the railroad as a whole from its beginning of operation in 1905 to the complete takeover by the Union Pacific in 1921. It operated under the title of the San Pedro Los Angeles & Salt Lake Railroad from

1905 to 1916. From 1916 to 1921 it operated under the name of the Los Angeles & Salt Lake Railroad.

Even though the Union Pacific had half ownership in the railroad from the beginning, it operated under its own name as the principal line which connected Salt Lake City to Los Angeles. Just as the Oregon Short Line operated under this name on their specific domain and was owned by the UP.

Technically all nails used on the OSL, SPLA&SL and the LA&SL could be considered Union Pacific nails as these roads were part of the UP’s empire. But many nails used by these railroads are unique to the line that used them. I believe that all nails from 1905 to 1916 can be listed correctly under the Salt Lake Route or San Pedro Los Angeles & Salt Lake Railroad. Nails between 1916 and 1921 are almost nonexistent with very few being found. Because of the lack of interest by the Clark group in paying for maintenance before the takeover and the war, I believe that both the UP and SLR were content with just keeping the railroad operating.

The SI (07) 14, SI (18) 15 and RR 2 ½ X .18 (07) 16 are rare and tough to find with the SI (18) 15 being extremely rare with only two known which were found in the Milford area. Two RI 2 ½ x ¼ (07) 17’s was reported to have been found in the Delta area. These could be from secondhand ties or an isolated effort to continue dating ties during that period. Arnold Smith found a RI 2 ½ x ¼ (01) 04 along the Topliff branch, but it was probably associated with the OSL who owned this branch until 1905. One would assume that the scarcity of nails after 1913 might be due to the fact that the Clark group became disinterested in their railroad and maintenance dwindled to a point where only necessary upkeep was performed just to keep the railroad operating.

The SLR, OSL and UP used some of the same nails from 1921 to 1936 when they discontinued dating ties. Nails specific to the SLR from this period are the 2 X ¼ RR (18A) 28 and the (18B) 27 and 29. The only nail specific to the OSL is the 2 X ¼ (07) 25. The SLR and OSL also used the (18A) 26 and (18B) 24 and 25 which the UP didn’t. The only nails that could possibly be considered LA & SL would be the

16 and 17. But my guess is that the 16 was the last attempt by the SPLA & SL to date ties but ceased to be used any longer sometime during that year. The 2 ½ X ¼ RI (07) 21 is an anomaly. I found it while tilling my garden when I lived in Cedar Fort, which was a whistle stop on the Salt Lake & Western (later SLR) Topliff branch. All nails and related railroad artifacts found in the area were strictly Salt Lake Route. The date fits into the time frame but is it definitely a SLR nail? It will stay in my set until I find out differently.

This is my personal collection of SPLA&SL and Union Pacific date nails. The only nails I am missing are the round indent (18B) 07, the square indent (07) 14 and (18) 15, the round raised (07) 16 and the 2 X ¼ RR (18B) 27. (The type (17) 36 is a

Union Pacific nail.)

time, the situation with the Santa Fe joint track usage agreement through Cajon Pass became intolerable. According to the agreement, the Santa Fe trains had priority for their trains through the pass resulting in aggravating delays for the SPLA&SL runs. The crush

of traffic on the Santa Fe lines through the pass led to the construction of several sections of second track. The first two miles from San Bernardino was in place by 1910. At the same time track was being laid from Barstow to Hicks (now Cottonwood). By 1912

the second line on the west slope reached Keenbrook. The following year a second track was extended to Cajon Pass and an entirely new line was built on a 2.2% grade from Cajon to Summit.

The Salt Lake Route brought its grievances against the Santa Fe to an I.C.C panel in 1915, and on January 16, 1916, the board drew up a new contract granting the SPLA equal usage of the joint track and the 60% tariff they were paying the SF for online business was abolished. It was finalized on February 1, 1916, and was to be effective for 99 years.

In 1916 another branch was started from Pico to Santa Ana but was interrupted due to the First World War. Also in 1916, an important change to the corporate title of the SPLA&SL took place. The city of San Pedro had been annexed by the city of Los Angeles

in 1909 and thus had no further significance. On August 16, 1916, the company’s official name changed, and it became the Los Angeles & Salt Lake RR Company.

With the threat of war present for several years, things still remained business as usual. But with the sinking of the Lusitania in 1917, the United States entered the war by declaring war on Germany. On December 28, 1917, the Federal Government took control of the nation’s railroads through the formation of the United States Railroad Administration. The SLR had little involvement or importance where the war was concerned and were more or less left unchanged. Due to the turmoil of the war, the use of different railroad properties became more liberal. The yards and roundhouses at Barstow, San Bernardino and Colton were used freely by both roads.

Even though the armistice was signed on November 11, 1918, the government didn’t return the railroads to their owners until March 1, 1920. The two years and three-month period of federal control did little damage to the LA&SL compared to other carriers, but

the Clark’s were losing interest in their half-ownership of the road. Senator W.A. Clark and his brother J. Ross Clark dominated the early management of the SLR, but after 1913 Senator Clark vigorously pursued other interests although he continued as president.

Perhaps he lost interest in his railroad because of the disasters and losses, or the loss of J. Ross Clark’s son on the Titanic.

This lack of interest was especially annoying to the Union Pacific. Six days after regaining control of the Los Angeles & Salt Lake from the government, plans were made to expand and speed up the railroad’s passenger service. Construction that was put on hold because of the war resumed. But the Clark’s, who still held 50% ownership, balked at coming up with their share of the funds to proceed. It was becoming more difficult to get the Clark’s to even spend enough money just for maintenance to help keep the property in safe condition. The UP was committed to the business of running a railroad and couldn’t abide the current situation much longer.

On April 27, 1921, an agreement was negotiated with W.A. Clark and his associates that would allow the Union Pacific to purchase the remaining half of the capital in the Los Angeles & Salt Lake RR for $2,500,000 in cash and s$29,511,000 in Union Pacific and

Southern Pacific mortgage bonds. Thus, the UP and the Oregon Short Line became joint owners of the LA&SL Company and drew up plans to develop the SLR to its full potential.

Summary

Senator Clark and his associates took a great risk to invest in the Salt Lake Route and see it through. There were many who called them wild speculators to embark on a project through vast areas of barren country. But the project had been carefully planned with an

eye to the future and the potential for great profits that could be reaped. Sadly, the profits hoped for didn’t materialize during the period that the Clark’s were connected with the railroad. Just after the Clark’s pulled out, the Salt Lake Route began a period of

tremendous growth.

Long after the Clark’s left the scene, the corporate title of the Los Angeles & Salt Lake Railroad Company remained and continued to be used for years to come. But after April 27, 1921, the Union Pacific had as much importance in Los Angeles as it did in Omaha.

Judge Robert S. Lovett, chairman of the executive committee of the Union Pacific System, made the following announcement in regard to the change in control:

“The logical and natural destiny of the Los Angeles & Salt Lake ultimately as a railroad property is as a part of the Union Pacific System; and appreciation of this and not any differences led to the sale. It is a rather remarkable fact that during the 18 years of equal joint ownership and control by Senator Clark and us absolutely no disagreements respecting policies, control or management have ever arisen between us. Our relations could not have been more co-operative and harmonious.”

The term Salt Lake Route slowly disappeared as time went on. Once the Clark group was out, the LA&SL was free to undergo the same vigorous development that was a trademark of Union Pacific properties in the west. Between January 1922 and January

1925, the UP spent more than twelve million dollars on betterments and new construction, including replacing all light tracks with 90-pound rail.

The following page is a reprint of an article by Jeff Oaks on the SLR, OSL & UP that was published in the Winter 2000 issue of the NN and adds additional information about the merging of the railroads:

The Nails

The name Salt Lake Route can refer to the railroad as a whole from its beginning of operation in 1905 to the complete takeover by the Union Pacific in 1921. It operated under the title of the San Pedro Los Angeles & Salt Lake Railroad from

1905 to 1916. From 1916 to 1921 it operated under the name of the Los Angeles & Salt Lake Railroad.

Even though the Union Pacific had half ownership in the railroad from the beginning, it operated under its own name as the principal line which connected Salt Lake City to Los Angeles. Just as the Oregon Short Line operated under this name on their specific domain and was owned by the UP.

Technically all nails used on the OSL, SPLA&SL and the LA&SL could be considered Union Pacific nails as these roads were part of the UP’s empire. But many nails used by these railroads are unique to the line that used them. I believe that all nails from 1905 to 1916 can be listed correctly under the Salt Lake Route or San Pedro Los Angeles & Salt Lake Railroad. Nails between 1916 and 1921 are almost nonexistent with very few being found. Because of the lack of interest by the Clark group in paying for maintenance before the takeover and the war, I believe that both the UP and SLR were content with just keeping the railroad operating.

The SI (07) 14, SI (18) 15 and RR 2 ½ X .18 (07) 16 are rare and tough to find with the SI (18) 15 being extremely rare with only two known which were found in the Milford area. Two RI 2 ½ x ¼ (07) 17’s was reported to have been found in the Delta area. These could be from secondhand ties or an isolated effort to continue dating ties during that period. Arnold Smith found a RI 2 ½ x ¼ (01) 04 along the Topliff branch, but it was probably associated with the OSL who owned this branch until 1905. One would assume that the scarcity of nails after 1913 might be due to the fact that the Clark group became disinterested in their railroad and maintenance dwindled to a point where only necessary upkeep was performed just to keep the railroad operating.

The SLR, OSL and UP used some of the same nails from 1921 to 1936 when they discontinued dating ties. Nails specific to the SLR from this period are the 2 X ¼ RR (18A) 28 and the (18B) 27 and 29. The only nail specific to the OSL is the 2 X ¼ (07) 25. The SLR and OSL also used the (18A) 26 and (18B) 24 and 25 which the UP didn’t. The only nails that could possibly be considered LA & SL would be the

16 and 17. But my guess is that the 16 was the last attempt by the SPLA & SL to date ties but ceased to be used any longer sometime during that year. The 2 ½ X ¼ RI (07) 21 is an anomaly. I found it while tilling my garden when I lived in Cedar Fort, which was a whistle stop on the Salt Lake & Western (later SLR) Topliff branch. All nails and related railroad artifacts found in the area were strictly Salt Lake Route. The date fits into the time frame but is it definitely a SLR nail? It will stay in my set until I find out differently.

This is my personal collection of SPLA&SL and Union Pacific date nails. The only nails I am missing are the round indent (18B) 07, the square indent (07) 14 and (18) 15, the round raised (07) 16 and the 2 X ¼ RR (18B) 27. (The type (17) 36 is a

Union Pacific nail.)

I am including with this article the Utah Nails List compiled by V. Arnold Smith. As of now it should be considered the definitive source of information on date nails used by the railroads which serviced the state of Utah.